Chapter Overview

"the initial impetus for research is the search for theory"

(Fawcett and Downs, 1986)

A chapter on theory as a research technique is strange as, in a way, what is academic research about if it is not about theory – without theory we may be engaged in product development, or data gathering, but not research. This said, there is of course also a spiritus mundi against theory: in abstracting away from the particular, theory is seen as at best simplistic and at worst reductionist and dangerous. And of course in popular language a theory is an unsubstantiated guess, almost the opposite of the scientific understanding of theory!

A theoretical approach is also not so much a method or technique that is applied to research, but an attitude and a desire to make sense of and to understand, in some ordered way, the phenomena around us. This approach can influence design and research methodology; indeed those most avowedly atheoretical in their methods are often most theoretical in their methodology!

Theories, that is systematic and structured bodies of knowledge, are the raw material for both research and practical design, but are also the outcomes of research and often the results of more informal reflection on experience. As we shall discuss shortly, theory is the language of generalisation, the way we move from one particular to another with confidence.

And theories are more basic still. A tiny baby watches her moving fingers, hits out at a ball and sees it move, gradually making sense of the relation between feelings and effects; the building, testing, and use of theory are as essential a part of our lives as feeding and breathing.

In HCI, developing, understanding and applying theory is particularly important. Technology and its use move so rapidly that today’s empirical results are outdated tomorrow. To be proactive rather than merely reactive and to produce research results that are useful beyond the end of the current project or PhD requires deeper knowledge and informed analysis.

In this chapter we will first spend some time examining what theory is about: why it is important, what it is and is not, and at different kinds of theory. We will then look at different ways of using theory in HCI practice and research and ways of producing new theories. These techniques will be demonstrated by a number of real examples in research and commercial practice. Finally we will look at some of the strengths and weaknesses of theoretical approaches and the way they relate to other techniques.

References

-

Card, S., Moran, T. and Newell, A. (1983). The Psychology of Human-Computer Interaction. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

-

Carroll, J. and Rosson, M. (1992). Getting around the task-artifact cycle: how to make claims and design by scenario. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 10(2):181–212.

-

Carroll, J., Ed. (2003). HCI Models, Theories, and Frameworks: Toward a Multidisciplinary Science. (Interactive Technologies), Morgan Kaufmann.

-

Dix, A. (1996–2007). Research and Innovation Techniques.

http://www.hiraeth.com/alan/topics/res-tech/ -

Dix, A., Beale, R. and Wood, A. (2000). Architectures to make Simple Visualisations using Simple Systems. Proceedings of Advanced Visual Interfaces - AVI2000, ACM Press, pp. 51-60. http://alandix.com/academic/papers/avi2000/

-

Dix, A. (2002). Teaching Innovation Keynote at Excellence in Education and Training Convention, Singapore Polytechnic, May 2002.

http://alandix.com/academic/talks/singapore2002/ -

Dix, A. (2007). Why examples are hard, and what to do about it. Interfaces, 72:16–18. Autumn 2007.

http://www.hcibook.com/alan/papers/examples-2007/ -

Ellis, G. and Dix, A. (2006). An explorative analysis of user evaluation studies in information visualisation. In Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Beyond Time and Errors: Novel Evaluation Methods for Information Visualization (Venice, Italy, May 23, 2006). BELIV '06. ACM Press, New York, NY, pp. 1-7.

http://alandix.com/academic/papers/beliv06-evaluation/ -

Fawcett, J. and Downs, F. (1986). The Relationship of Theory and Research. Norwalk, CT: Appleton Century Crofts.

-

Fitts, P. (1954). The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 47(6):381–391. (Reprinted in Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 121(3):262--269, 1992).

-

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

-

Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine.

-

Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkle and Ethnomethodology. Polity Press, Cambridge, Mass, USA.

-

Keele. S. (1968). Movement Control in Skilled Motor Performance. Psychological Bulletin. 70:387–402.

-

Kuhn, T. (1962/1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1962, 1st edition; 1970, 2nd edition, with postscript).

-

Long, J. and Dowell, J. (1989). Conceptions of the Discipline of HCI: Craft, Applied Science, and Engineering. In: Sutcliffe, Alistair and Macauley, Linda (eds.) Proceedings of the HCI89 - People and Computers V, Cambridge University Press. pp. 9-32.

-

Meyer, D., Abrams, R., Kornblum, S., Wright, C., and Smith, J. (1988). Optimality in human motor performance: Ideal control of rapid aimed movements. Psychological Review, 95:340–370.

-

Minsky, M. (1965). Matter, Mind and Models. Proc. International Federation of Information Processing Congress 1965, Volume 1, pp. 45–49. http://web.media.mit.edu/~minsky/papers/MatterMindModels.html

-

OED (1973). Theory (definition). The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles. Third Edition. Volume II. W. Little, H. Fowler, J. Coulson C. Onions, G. Friedrichsen (eds.), Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 2281.

-

Plain English Campaign (2003). Foot in Mouth Award 2003. (accessed 26 July 2007). http://www.plainenglish.co.uk/footinmouth.htm#2003

-

Popper, K. (1959). The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Basic Books, New York, NY, 1959.

-

Suchman, L. (1987). Plans and Situated Actions: the problem of human-machine communication. Cambridge University Press.

-

Winograd, T. and Flores, F. (1985). Understanding Computers and Cognition. Ablex Publishing Corp.

|

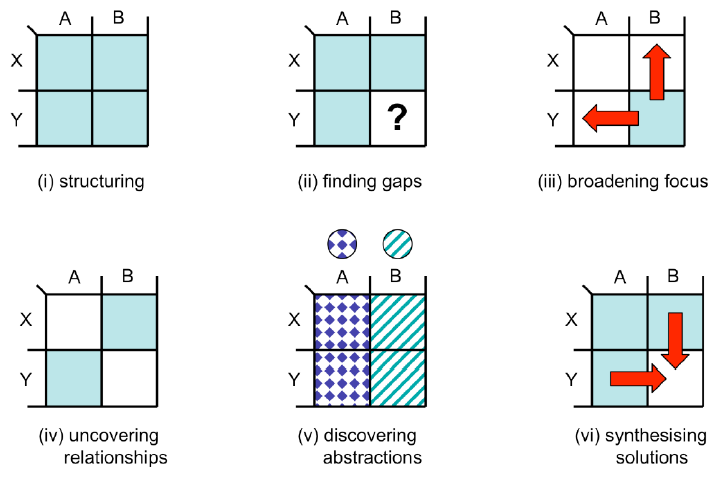

Figure 1. Uses of multiple classification (from Dix, 2002)

[ zoom image ]

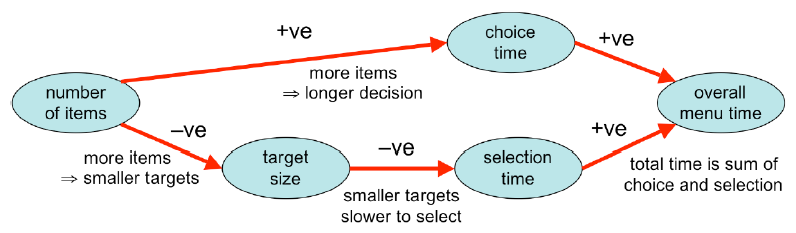

Figure 2. Network of influences of number of items shown on screen

[ zoom image ]

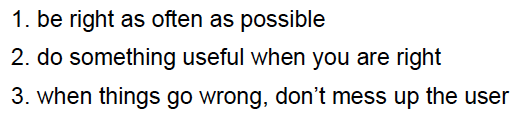

Figure 3. The three rules of Appropriate Intelligence (Dix et al., 2000)

[ zoom image ]

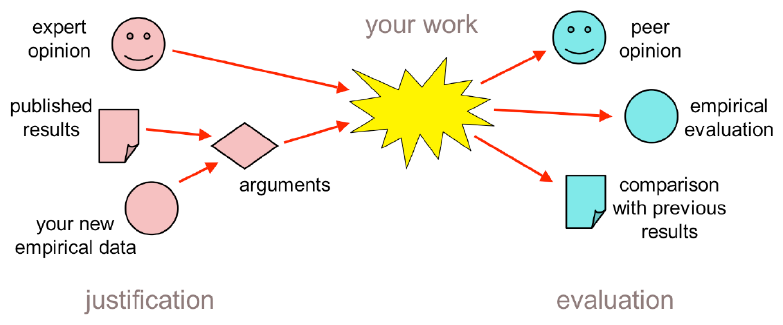

Figure 4. Validation from two sides

[ zoom image ]