Abstract

This paper explores the topic of exploration (sic) within the design space and discusses how this can support the development of research design. It highlights the relevance of reflecting upon the exploration of the design space and briefly introduces a set of techniques that can be used for this.

Keywords: Design research, design space, idea generation, reflection in action

INTRODUCTION

Current understanding and practice of interaction design has limitations which explain the challenges that this field encounters in order to meet the ever increasing demands of information technology.

Such challenges are primarily due to our limited understanding of what design is and how it really occurs. A large amount of work is being carried out to unfold the craftsmanship dimension of design and better articulate practitioners’ knowledge in codes of best practices [8],[13],[15]. Such codes would facilitate the acquisition of practical skills in industrial settings, and more importantly, become an integral part of academic training.

Despite the efforts deployed in this direction, the academic study of design is still in its infancy. In order to elevate the study of the design from the status of art and craft to one of science, a leap from practice to theory should be made. For this, researchers should develop theories through articulation and inductive inquiry [6].

In the context of craftsmanship it is worth mentioning the distinction between procedural knowledge and declarative knowledge, that has long been acknowledged in many theories of learning and cognition [12]. Declarative knowledge is knowledge that people can report and of which they are consciously aware. Offering a descriptive representation of knowledge, declarative knowledge expresses facts, like what things are [14]. On the other hand, procedural knowledge is that knowledge that people cannot verbalize. They form part of a mental model which enables the execution of some tasks because of the technical skills capturing the “knowing-how” [2]. Because of the lack of awareness characterizing it, procedural knowledge is usually taken for granted [1].

The successful development of design field requires both declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge. Part of the challenge of the theoretical accounts for design is to unfold the procedural knowledge embedded in tacit practice and lift this to the level of declarative knowledge (see also [6]).

EXPLORING DESIGN SPACE

The topic we propose for this workshop relates to the efficient exploration of the design space and puts forward the following questions:

- What constitute an exploration?

- Is the exploration of some specific (possibly odd) places within the design space more useful as opposed to random exploration?

- Which are the techniques for identifying such specific odd places?

Traditional design often proceeds by generating ideas which are assessed so that the one that best meets the design constraints is further incrementally improved and ultimately implemented. This approach of many small steps limits the exploration of the design space and it is also problematic within truly novel domains. A challenge for design is to generate initial ideas which are better, more novel or more provocative to our understanding.

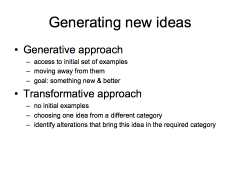

Ways of generating ideas to support a particular design problem include:

- Generative approaches are applied when the thinker has access to a set of examples that can address the problem but wishes to move away from them and discover something new and better. It involves the identification of all those examples and an analysis of how each of them succeeds or fails to address the design constraints. This analysis will support the elaboration of a new, hybrid idea able to account for more than the original ideas.

- Transformative approaches are applied when there are no examples to address a design problem. In this case, the person takes a single (alien) example from a different (although often related) category or problem domain and identify a series of alterations that bring the alien ideas into the desired category [5].

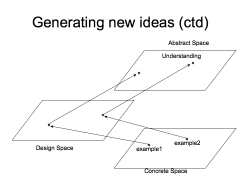

Idea generation and evaluation is a process which involves two planes: the abstract and the concrete. The abstract plane involves reflection and understanding, while the concrete plane involves artifacts, examples or ideas.

A good exploration of the design space will allow fluid movements between these two planes, where examples are used to gain a better understanding which in turn is used to generate or refine concrete ideas. The points in the design space do not necessarily have an intrinsic value, (e.g. labeled as good or bad) but they become relevant for enabling the understanding of the significant dimensions within the design space.

Such fluid movements between these two planes can occur through acting in the physical plane and reflecting upon it in order to reach understanding and the associated abstractions required in the abstract plane. Constructivism and reflection in action are two theoretical frameworks that account for this. Constructivism is an approach to learning which considers that people construct their own understanding through experiencing things and reflecting on their experience [10]. Through this reflection component, constructivism is related to “reflection in action” approach [11], but it does not necessarily require action. Building on constructivism, experiential learning is an approach which considers fours stages of learning: concrete experience, reflection, abstract conceptualization and active experimentation [9].

The benefits of bridging the two planes and the associated relevance of this topic are outlines below.

TOPIC RELEVANCE

The efficient exploration of the design space will lead to the identification of new points within it. The evaluation of these points will enable the understanding of the relevant features underlying the design space. Evaluating does not refer to assigning values to these points but to identify how much such points reveal about the design space and therefore support its understanding.

The exploration of the design space could support both generalization and prediction for developing designs within the same class of requirements. This relates to reproducing the design process and anticipating its outcome. The fluid movements between the concrete and abstract planes facilitate the development of descriptive knowledge, e.g. why things are like they are; predictive knowledge, e.g. what is the outcome for a given condition; and more importantly, synthetic knowledge, e.g. what are the conditions for a desirable outcome.

TECHNIQUES FOR EXPLORING THE DESIGN SPACE

This section introduces three techniques aiming to support the efficient exploration of the design space whose benefits were outlined above.

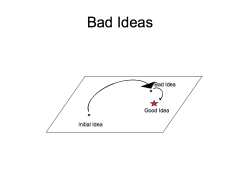

Bad ideas

This technique capitalizes on often accidental way in which bad ideas become beneficial detours enlarging the pool of good ideas aiming to solve a particular problem [4]. Instead of these being accidents, participants are encouraged to deliberately create bad ideas and these are systematically analyzed. Bad ideas encourage both divergent thinking and a more structured analysis of the problem. Through its inner features, e.g. impossible, impractical, or just absurd, a bad idea pulls the person to a new, unpredictable place within the design space. The benefits of this technique reside in developing good ideas from the bad ones, with the support of three prompts: exploring the good aspects of the bad idea, changing the context where the bad idea can become a good one, and role play for engaging in the exploration of bad ideas. Because bad ideas usually violate the design goals or constraints, this process enables the articulation of dimensions and properties of the design space.

Besides supporting critical thinking, bad ideas enable the exploration and even more important, the understanding of the design space, by reducing also the emotional attachment that people usually develop towards their good ideas.

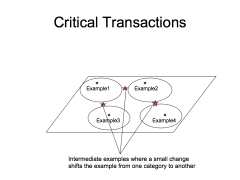

Critical transitions

This method consists in identifying key points within the design space, e.g. prototypical examples for various categories, and then trying to identify intermediate examples together with the categories they belong to. This allows the identification of those points of transition where a small change shifts the example from one category to another. By doing this one can discover the attribute that changed and thus became critical for a given category [3].

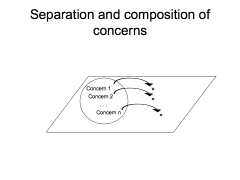

Separation and composition of concerns

This method focuses on addressing sequentially each design constraint and requirement and generating ideas that address them. This initial stage where the concerns are addressed in isolation is followed be a second stage where

the interaction and interdependency between design constraints are addressed. This technique supports a generative approach to idea generation.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper introduces the topic of design space exploration together with its benefits and three techniques for addressing it. It aims to provoke insightful exchange of ideas in this workshop theme on design research.

REFERENCES

- Ambrosini, V. and Bowman, C. Tacit knowledge: Some suggestions for operationalization. Journal of Management Studies, 38(6), (2001). 811–829.

- Anderson, J. Cognitive Psychology and Its Implications. Worth Publishing, New York, NY. (2000).

- Dix, A. Paths and Patches - patterns of geognosy and gnosis. In Spaces, Spatiality and Technology. Napier University Edinburgh. (2004) http://www.hcibook.com/alan/papers/space2-2004

- 4. Dix, A., Ormerod,T., Twidale, M., Sas, C., Gomes da Silva, P.A. and McKnight, L. Why Bad Ideas are a Good Idea. HCI Educators Workshop. (2006).

- Dix, A. Being Playful – learning from children. Interaction Design and Children. Preston, UK (2003).

- Friedman, K. Theory construction in design research: criteria: approaches, and methods. Design Studies, 24 (2003), 507–522

- Gries, M. Methods for Evaluating and Covering the Design Space during Early Design Development, Electronics Research Lab, University of California at Berkeley, Tech. Rep. UCB/ERL M03/32. (2003). URL: citeseer.ist.psu.edu/article/gries04methods.html

- Kehoe, C. (2001). Supporting Critical Design Dialog, Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. Georgia Institute of Technology.

- Kolb. D. A. and Fry, R. (1975). Toward an applied theory of experiential learning, in C. Cooper (ed.) Theories of Group Process, London: John Wiley.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press

- Schön, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. Jossey Bass, London.

- Slusarz, P. and Sun, R. (2001). The interaction of explicit and implicit learning: An integrated model. In Proceedings of the 23rd Cognitive Science Society Conference, pages 952–957, Mahwah, NJ. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Strong, G., Gasen, J.B. Hewett, T., Hix, D., Morris, J., Muller, M.J. and Novick, D.G. (1994). New Directions in HCI Education, Research, and Practice. Washington, DC: NSF/ARPA.

- Turban, E. and Aronson, J. (1998). Decision Support System and Intelligent Systems. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Wroblewski, D.A. (1991). The construction of human- computer interfaces considered as a craft. In J. Karat (Ed.), Taking software design seriously (pp. 1-19). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

|