I’ve been wondering about the broader copyright implications of a case that went through the England and Wales Court of Appeal earlier this year. The case was brought by the NLA (Newspaper Licensing Agency) against Meltwater, who run commercial media-alert services; for example telling you or your company when and where you have been mentioned in the press.

While the case is specifically about a news service, it appears to have broader implications for the web, not least because it makes new judgements on:

- the use of titles/headlines — they are copyright in their own right

- the use of short snippets (in this case no more than 256 characters) — they too potentially infringe copyright

- whether a URL link is sufficient acknowledgement of copyright material for fair use – it isn’t!

These, particularly the last, seems to have implications for any form of publicly available lists, bookmarks, summaries, or even search results on the web. While NLA specifically allow free services such as Google News and Google Alerts, it appears that this is ‘grace and favour’, not use by right. I am reminded of the Shetland case, which led to many organisations having paranoid policies regarding external linking (e.g. seeking explicit permission for every link!).

So, in the UK at least, web law copyright law changed significantly through precedent, and I didn’t even notice at the time!

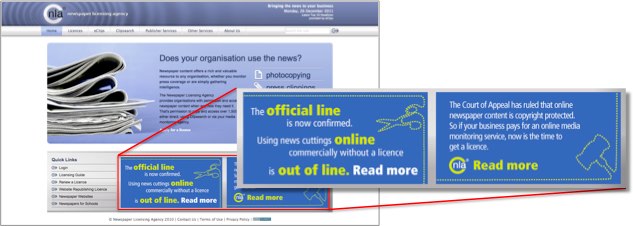

In fact, the original case was heard more than a year ago November 2010 (full judgement) and then the appeal in July 2011 (full judgement), but is sufficiently important that the NLA are still headlining it on their home page (see below, and also their press releases (PDF) about the original judgement and appeal). So effectively things changed at least at that point, although as this is a judgement about law, not new legislation, it presumably also acts retrospectively. However, I only recently became aware of it after seeing a notice in The Times last week – I guess because it is time for annual licences to be renewed.

Newspaper Licensing Agency (home page) on 26th Dec 2011

The actual case was, in summary, as follows. Meltwater News produce commercial media monitoring services, that include the title, first few words, and a short snippet of news items that satisfy some criteria, for example mentioning a company name or product. NLA have a license agreement for such companies and for those using such services, but Meltwater claimed it did not need such a license and, even if it did, its clients certainly did not require any licence. However, the original judgement and the appeal found pretty overwhelmingly in favour of NLA.

In fact, my gut feeling in this case was with the NLA. Meltwater were making substantial money from a service that (a) depends on the presence of news services and (b) would, for equivalent print services, require some form of licence fee to be paid. So while I actually feel the judgement is fair in the particular case, it makes decisions that seem worrying when looked at in terms of the web in general.

Summary of the judgement

The appeal supported the original judgement so summarising the main points from the latter (indented text quoting from the text of the judgement).

Headlines

The status of headlines (and I guess by extension book titles, etc.) in UK law are certainly materially changed by this ruling (para 70/71), from previous case law (Fairfax, Para. 62).

Para. 70. The evidence in the present case (incidentally much fuller than that before Bennett J in Fairfax -see her observations at [28]) is that headlines involve considerable skill in devising and they are specifically designed to entice by informing the reader of the content of the article in an entertaining manner.

Para. 71. In my opinion headlines are capable of being literary works, whether independently or as part of the articles to which they relate. Some of the headlines in the Daily Mail with which I have been provided are certainly independent literary works within the Infopaq test. However, I am unable to rule in the abstract, particularly as I do not know the precise process that went into creating any of them. I accept Mr Howe’s submission that it is not the completed work as published but the process of creation and the identification of the skill and labour that has gone into it which falls to be assessed.

Links and fair use

The ruling explicitly says that a link is not sufficient acknowledgement in terms of fair use:

Para. 146. I do not accept that argument either. The Link directs the End User to the original article. It is no better an acknowledgment than a citation of the title of a book coupled with an indication of where the book may be found, because unless the End User decides to go to the book, he will not be able to identify the author. This interpretation of identification of the author for the purposes of the definition of “sufficient acknowledgment” renders the requirement to identify the author virtually otiose.

Links as copies

Para 45 (not part of the judgement, but part of NLA’s case) says:

Para. 45. … By clicking on a Link to an article, the End User will make a copy of the article within the meaning of s. 17 and will be in possession of an infringing copy in the course of business within the meaning of s. 23.

The argument here is that the site has some terms and conditions that say it is not for ‘commercial user’.

As far as I can see the judge equivocates on this issue, but happily does not seem convinced:

Para 100. I was taken to no authority as to the effect of incorporation of terms and conditions through small type, as to implied licences, as to what is commercial user for the purposes of the terms and conditions or as to how such factors impact on whether direct access to the Publishers’ websites creates infringing copies. As I understand it, I am being asked to take a broad brush approach to the deployment of the websites by the Publishers and the use by End Users. There is undoubtedly however a tension between (i) complaining that Meltwater’s services result in a small click-through rate (ii) complaining that a direct click to the article skips the home page which contains the link to the terms and conditions and (iii) asserting that the End Users are commercial users who are not permitted to use the websites anyway.

Free use

Finally, the following extract suggests that NLA would not be seeking to enforce the full licence on certain free services:

Para. 20. The Publishers have arrangements or understandings with certain free media monitoring services such as Google News and Google Alerts whereby those services are currently licensed or otherwise permitted. It would apparently be open to the End Users to use such free services, or indeed a general search engine, instead of a paid media monitoring service without (currently at any rate) encountering opposition from the Publishers. That is so even though the End Users may be using such services for their own commercial purposes. The WEUL only applies to customers of a commercial media monitoring service.

Of course, the fact that they allow it without licence, suggests they feel the same copyright rules do apply, that is the search collation services are subject to copyright. The judge does not make a big point of this piece of evidence in any way, which would suggest that these free services do not have a right to abstract and link. However, the fact that Meltwater (the agency NA is acting against) is making substantial money was clearly noted by the judge, as was the fact that users could choose to use alternative services free.

Thinking about it

As noted my gut feeling is that fairness goes to the newspapers involved; news gathering and reportingis costly, and openly accessible online newspapers are of benefit to us all; so, if news providers are unable to make money, we all lose.

Indeed, years ago in dot.com days, at aQtive we were very careful that onCue, our intelligent internet sidebar, did not break the business models of the services we pointed to. While we effectively pre-filled forms and submitted them silently, we did not scrape results and present these directly, but instead sent the user to the web page that provided the information. This was partly out a feeling that this was the right and fair thing to do, partly because if we treated others fairly they would be happy for us to provide this value-added service on top of what they provided, and partly because we relied on these third-party services for our business, so our commercial success relied on theirs.

Indeed, years ago in dot.com days, at aQtive we were very careful that onCue, our intelligent internet sidebar, did not break the business models of the services we pointed to. While we effectively pre-filled forms and submitted them silently, we did not scrape results and present these directly, but instead sent the user to the web page that provided the information. This was partly out a feeling that this was the right and fair thing to do, partly because if we treated others fairly they would be happy for us to provide this value-added service on top of what they provided, and partly because we relied on these third-party services for our business, so our commercial success relied on theirs.

This would all apply equally to the NLA v. Meltwater case.

However, like the Shetland case all those years ago, it is not the particular of the case that seems significant, but the wide ranging implications. I, like so many others, frequently cite web materials in blog posts, web pages and resource lists by title alone with the words live and pointing to the source site. According to this judgement the title is copyright, and even if my use of it is “fair use” (as it normally would be), the use of the live link is NOT sufficient acknowledgement.

Maybe, things are not quite so bad as they seem. In the NLA vs. Meltwater case, the NLA had a specific licence model and agreement. The NLA were not seeking retrospective damages for copyright infringement before this was in place, merely requiring that Meltwater subscribe fully to the licence. The issue was not that just that copyright had been infringed, but that it had been when there was a specific commercial option in place. In UK copyright law, I believe, it is not sufficient to say copyright has been infringed, but also to show that the copyright owner has been materially disadvantaged by the infringement; so, the existence of the licence option was probably critical to the specific judgement. However the general principles probably apply to any case where the owner could claim damage … and maybe claim so merely in order to seek an out-of-court settlement.

This case was resolved five months ago, and I’ve not heard of any rush of law firms creating vexatious copyright claims. So maybe there will not be any long-lasting major repercussions from the case … or maybe the storm is still to come.

Certainly, the courts have become far more internet savvy since the 1990s, but judges can only deal with the laws they are give, and it is not at all clear that law-makers really understand the implications of their legislation on the smooth running of the web.

Faranheit 451 is about a future where books are burnt because they have increasingly been regarded as meaningless by a public focused on quick fix entertainment and mindless media: censorship more the result than the cause of societal malaise.

Faranheit 451 is about a future where books are burnt because they have increasingly been regarded as meaningless by a public focused on quick fix entertainment and mindless media: censorship more the result than the cause of societal malaise.