A colleague recently said to me “As computer scientists, our index always starts with a 0“, and my immediate thought was “not when I was a lad“!

As well as revealing my age, this is an interesting reflection on the evolution of programming languages, and in particular the way that programming languages in some ways have regressed in terms of human-centredness expecting the human to think like a machine, rather than the machine doing the work.

But let’s start with array indices. If you have programmed arrays in Java, Javascript, C++, PHP, or (lists in) Python they all have array indices starting at 0: a[0],,a[1], etc. Potentially a little confusing for the new programmer, an array of size 5 therefore has last index 4 (five indices: 0,1,2,3,4). Also code is therefore full of ‘length-1’

double values[] = codeReturningArray(); double first = values[0]; double last = values[values.length-1];

This feels so natural we hardly notice we are doing it. However, it wasn’t always like this …

The big three early programming languages were Fortran (for science), Algol (for mathematics and algorithms) and COBOL (for business). In all of these arrays/tables start at 1 by default (reflecting mathematical conventions for matrices and vectors), but both Fortran and Algol could take arbitrary ranges – the compiler did the work of converting these into memory addresses.

Another popular early programming language was BASIC created as a language for learners in 1964, and the arrays in the original Basic also started at 1. However, for anyone learning Basic today, it is likely to be Microsoft Visual Basic used both for small business applications and also scripting office documents such as Excel. Unlike the original Basic, the arrays in Visual Basic are zero based arrays ending one less than the array size (like C). Looking further into the history of this, arrays in the first Microsoft Basic in 1980 (a long time before Wiindows) allowed 0 as a start index, but

Dim A(10) meant there were 11 items in the array 0–10. This meant you could ignore the zero index if you wanted and use A(1..10) like in earlier BASIC, Fortran etc, but meaning the compiler had to do less work.In both Pascal and Ada, arrays are more strongly typed, in that the programmer explicitly specifies the index range, not simply a size. That is, it is possible to declare zero-based arrays A[0..9], one-based arrays A[1..7] or indeed anything else A[42..47]. However, illustrative examples of both Pascal arrays and Ada arrays typically have index types stating at 1 as this was consistent with earlier languages and also made more sense mathematically.

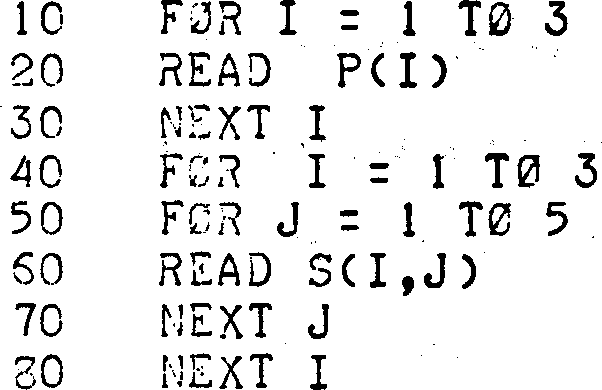

It should be noted that most of the popular early language also allowed matrices or multi-dimensional arrays,

Fortran: DIMENSION A(10,5) Algol: mode matrix = [1:3,1:3]real; Basic: DIM B(15, 20) Pascal: array[1..15,1..10] of integer;

So, given the rich variety of single and multi-dimensional arrays, how is it that arrays now all start at zero? Is this the result of deep algebraic or theoretical reflection by the computer science community? In fact the answer is far more prosaic.

Most modern languages are directly or indirectly influenced by C or one of its offshoots (C++, Java, etc.), and these C-family languages all have zero indexed arrays because C does.

I think this comes originally from BCPL (which I used to code my A-level project at school) which led to B and then C. Arrays in BCPL were pointer based (as in C) making no distinction between array and pointer. BCPL treated an ‘array’ declaration as being memory allocation and ‘array access (array!index) as pointer arithmetic. Hence the zero based array index sort of emerged.

This was all because the target applications of BCPL were low-level system code. Indeed, BCPL was intended to be a ‘bootstrap’ language (I think the first language where the compiler was written in itself) enabling a new compiler to be rapidly deployed on a new architecture. BCPL (and later C) was never intended for high-level applications such as scientific or commercial calculations, hence the lack of non-zero based arrays and proper multi-dimensional arrays.

This is evident in other areas beyond arrays. I once gave a C-language course at one of the big financial institutions. I used mortgage calculation as an example. However, the participants quickly pointed out that it was not a very impressive example, as native integers were just too small for penny-accurate calculations of larger mortgages. Even now with a 64 bit architecture, you still need to use flexible-precision libraries for major financial calculations, which came ‘for free’ in COBOL where numbers were declared at whatever precision you wanted.

Looking back with a HCI hat on, it is a little sad to see the way that programming languages have regressed from being oriented towards human understanding with the machine doing the work to transform that into machine instructions, towards languages far more oriented towards the machine with the human doing the translation 🙁

Maybe it is time to change the tide.