Water has been at the heart of Welsh politics for many years as highlighted by an article in the BBC News today1. However, the impacts of climate change means this is a growing issue across the world.

BBC News: Wales ‘missing out on fortune’ over water powers – An ex-minister says he is “aghast” the Welsh government still hasn’t taken control of water policy.

I recall hearing on the radio about the Free Wales Army attacking water pipelines in the 1960s. I was a small child at the time and thought it all sounded very exciting, but I had no idea of the politics behind this.

It was brought home to me when I first paid water rates myself.

As a child, after my dad died, my mum was incredibly good at managing the finances and saving for bills. Each year the household rate bill would arrive (the UK housing tax for local services). It would be huge, but as she was on widow’s benefit there was a rebate of 90% of the bill, so the remainder was manageable. However, this did not include water and sewage. Once a year the water rates bill would arrive. It was as big as the standard ‘rates’ bill, but this time there was no rebate, and at that time there was no monthly payment option. As I said, mum was good at saving towards these big bills, but it was so big, we always knew when it hit the carpet!

Roll on the years and I am paying my own water rates bill for the first time in the early 1980s. We lived in Bedfordshire, a county of England not known for high rainfall. My water rates bill was £60 (about £300 today’s prices), but when I talked to my mum, in Cardiff, at the base of the Brecon Beacons with multiple reservoirs, her water bill was £300 (~£1500 today), five times higher.

The reason for this was that the water companies were semi-autonomous. Wales is full of mountains and consequently expensive to pipe water around the country, hence the high bills. However, Wales also has lots of water, but as this was piped across the border, there was no commensurate flow of cash back.

Happily this disparity no longer seems to be the case, I assume due to different subsidies to the water companies, but certainly highlights why the control of water is a political issue.

Separating the Waters

In the early months of 2020 the news in the UK was dominated by flooding; Covid-19 was still a distant and uncertain problem compared to the images of homes, shops, and whole communities inundated, often with filthy water contaminated by effluent forced out of drains and sewers. In insurance terms, flood is one of the natural disasters commonly referred to as “Acts of God”. Water seems to be the ultimate blessing or curse of God: the “rain falls on the just and the unjust” (Matt. 5:45) a liberal outpouring for all.

At the same time in the east of Australia bushfire raged, following an unprecedented heat wave. A little further west, in the Murray Darling Basin, a report highlighted that gigalitres of water were being wasted as large volumes of water were directed through the constricted river to almond groves near the sea, by-passing farms ravaged by drought on the way. Farmers looked on helpless as water flowed past by their parched land2.

Guardian 25 May 2019. Tough nut to crack: the almond boom and its drain on the Murray-Darling – Demand for the thirsty crop has created a gold rush but irrigators and growers fear there might not be enough water

As the coronavirus lockdown restricted movement across the world, it highlighted the plight of 15 million US citizens who each year have their water supply cut off for non-payment of water bills. In the UK water companies can sue and eventually bailiffs seize goods, but they cannot, by law, turn off the water supply. Water is deemed essential for human life and dignity. Not so in the US.

In normal times this is bad enough, but at least family members can use toilets and wash in their workplace or public buildings. However during lock down, confined in one’s home, there was no such recourse; bottled water could be brought in, but without a water supply faeces had to be collected and thrown out with the rubbish. One BBC report told the harrowing story of a woman with a family of eleven, who refused to let helpers drop off water at her home for shame of the smell.

How does water, the universal gift of God, become a commodity and privilege?

Water is not mentioned explicitly in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), but Article 25 guarantees the right to:

“a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care”

In addition, Article 22’s right to “social security” and the “economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality” seems highly pertinent.

Although the order of the 30 articles in the UDHR is not a priority list, it is perhaps telling that Article 25 comes well behind Article 17 which guarantees the right to private property.

Water and War

For many years there have been warnings of the impact of climate change on water supplies and the potential for conflict. Sometimes this is largely within states as in the case of Australia and the Colorado River in the US (although the latter also impacts North Mexico). However others cross national borders, such as the long-running disputes on the Nile, including between Egypt and Ethiopia about the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. There have always been water wars, but the likelihood and severity are expected to rise.

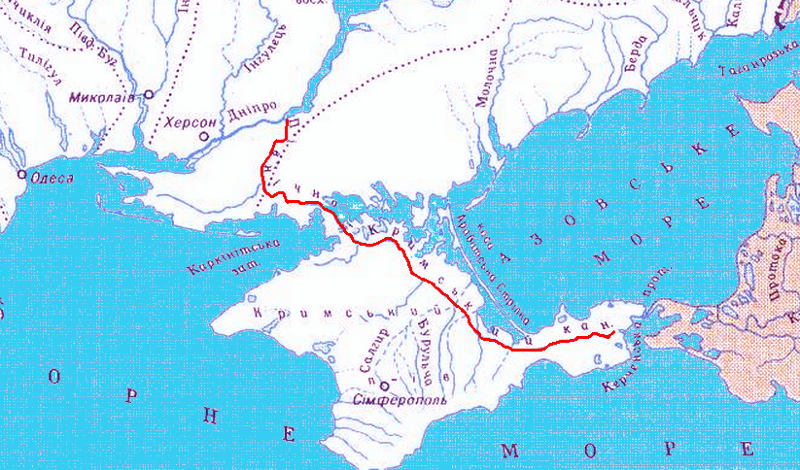

It was significant that one of the first actions of the Russian invasion into Ukraine was to reopen the North Crimean Canal, which had been dammed by the Ukrainian government in 2014 cutting off the majority of the fresh water supply to the two and half million people of the Crimean peninsula. The crisis was largely silent for many years, perhaps in part because Russia does not like to admit weakness, but back in 2020 there were warnings from open source news sites of the ever growing human, ecological and geopolitical crisis. and by 2021 this was picked by Bloomberg and the FT, the latter describing it as a ‘water war‘. Although there are many interlinked reasons for the conflict in Ukraine, it may be we are already seeing the first major modern water war.

- Thanks to Alan Sandry for pointing out the BBC article.[back]

- See 9News “Struggling Aussie farmers enraged by incredible water wastage” and full Australia Institute report “Southern discomfort: water losses in the southern Murray Darling Basin“.[back]