By Huynh Cong Ut (also known as Nick Ut), image from Wikipedia

From the ‘Napalm Girl‘ in Vietnam, to Alan Kurdi’s body on a Turkish beach in 2015 and endless images of White Hat’s pulling children from the rubble in Aleppo, it is easy to become inured to the death of innocent children around the world.

In the church calendar, December 28th1 is the Feast of the Innocents or Childermas, a day to remember the children killed by King Herod as he sought the baby Jesus.

In Matthew’s Gospel we read:

When Herod realized that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious, and he gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under (Matt. 2:16, NIV).

However, for many it is the words in the Christmas carol, “Unto us a boy is born“, which is most familiar:

All the little boys he killed at Bethlehem in his fury.

Mary and Joseph had already fled, refugees to Egypt, so the babies were not simply slaughtered, but slaughtered in vain, an action missing its true target, like the bombs that killed Gaddaffi’s children and grandchildren in 1986 and 2011.

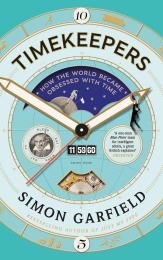

I’ve been reading Simon Garfield’s “Timekeepers‘ (a Christmas gift). Garfield describes a meeting with Nick Ut, the photographer of ‘Napalm Girl’2. The common story is that the US attack on the village from which Phan Thi Kim Phuc was running was a mistake, but Ut describes how in the village there were many dead Viet Cong, so that the mistake was more likely inadequate intelligence that the villagers had fled (Timekeepers, p.168).

I’ve been reading Simon Garfield’s “Timekeepers‘ (a Christmas gift). Garfield describes a meeting with Nick Ut, the photographer of ‘Napalm Girl’2. The common story is that the US attack on the village from which Phan Thi Kim Phuc was running was a mistake, but Ut describes how in the village there were many dead Viet Cong, so that the mistake was more likely inadequate intelligence that the villagers had fled (Timekeepers, p.168).

A few weeks ago a BBC reporter in Yemen was visiting a school, which Saudi air strikes had repeatedly hit. This was one example of many such incidents targeting schools during this conflict3. The reporter talked of how the school kept on working and pupils kept attending, despite the damage and the danger. However, the report also showed the Houthi rebel arms dump next to the school. “Can’t you move the school away from this?”, asked the reporter. “They would simply move the dump to follow us”, replied the headmaster.

Again this is a story we have heard so many times before: missiles fired from hospital grounds in Gaza, Ukraine keeping its air corridors open whilst in the midst of its air campaign against separatists4, ISIS preventing civilian evacuation from Mosul, or the South Korean artillery firing into disputed areas from a populated island.

In some cases civilians are deliberately put in the way of danger (as with ISIS); in others fighting in built up areas makes civilian presence inevitable (Aleppo, Gaza). In some cases terror is the main aim of an attack or the civilians are seen as legitimate targets (as with ISIS attacks in Europe); in others terror is a deliberate secondary war aim (as with Dresden or Nagasaki). In some cases attackers seem to show flagrant disregard for civilian life (as in Gaza), and in others all care is take, but (often substantial) civilian deaths are accepted as collateral damage (probably the case with US drone extrajudicial killings).

Whether you blame those on the ground for using human shields or those attacking for disregarding human like, often depends on which side you are on5.

In most conflicts the truth is complex, especially where there are mismatches of firepower: Hamas in Gaza, anti-Assad rebel groups in Syria, or ISIS in Iraq would all have been slaughtered if they fought in the open. And for the attacking side, where does the responsibility lie between callous disregard for human life and justifiable retaliation? How do we place the death of children by bombs against those of starvation and illness caused by displaced populations, siege or international sanctions?

If the events in Bethlehem were to happen today, how would we view Herod?

Was he despotic dictator killing his own people?

Was the baby Jesus a ‘clear and present danger’, to the stability the state and thus the children of Bethlehem merely collateral damage?

Or were Mary, Joseph and God to blame for using human shields, placing this infant of mass disruption in the midst of a small town?

It is worryingly easy to justify the slaughter of a child.

Some organisations that are making a difference:

- Save the Children Fund — working across the world to help children in need

- UNICEF — general relief including child refugees in Syria, “one of the most dangerous places to be a child”

- Tear Fund “No Child Taken” — preventing child trafficking

- The date varies in different churches, it is 28th December in most Western churches, but 27th, 29th Dec, or 10th January elsewhere[back]

- The ‘Napalm Girl’ recent obtained fresh notoriety when Facebook temporarily censored it because it showed nudity.[back]

- Another BBC report,amongst many, “Yemen crisis: Saudi-led coalition ‘targeting’ schools” documents this.[back]

- Before MH17 was shot down a Ukrainian military transport and other military planes had been shot down, and the first messages following the destruction of MH17 suggest the rebels thought they had downed another military aircraft. Instead of re-routing flights the flying ceiling was raised, but still within distance of ground-to-air missiles, and carriers made their own choices as to whether to overfly. Some newspapers suggest that the motives were mainly financial both for Malaysian Airways, and for the Ukrainian government decisions, rather than Ukraine using civilian flights as a deliberate human shield.[back]

- Patrick Cockburn’s comparison of Aleppo and Mosul in The Independent argues this is the case for the current conflicts in Syrian and Iraq.[back]