Over the past few weeks I’ve been to two conferences focused on different aspects of technology and learning, Talis Insight Europe and ACM Learning at Scale (L@S). This led me to reflect on the potential for and barriers to ground breaking research in these areas in the UK.

The first conference, Talis Insight Europe, grew out of the original Talis User Group, but as well as company updates on existing and new products, also has an extensive line-up of keynotes by major educational visionaries and decision makers (including pretty much the complete line-up of JISC senior staff) and end-user contributed presentations.

The second, Learning @ Scale, grew out of the MOOC explosion, and deals with the new technology challenges and opportunities when we are dealing with vast numbers of students. It also had an impressive array of keynote speakers, including Sugata Mitra, famous for the ‘Hole in the Wall‘, which brought technology to street children in India.

The second, Learning @ Scale, grew out of the MOOC explosion, and deals with the new technology challenges and opportunities when we are dealing with vast numbers of students. It also had an impressive array of keynote speakers, including Sugata Mitra, famous for the ‘Hole in the Wall‘, which brought technology to street children in India.

Although there were some common elements (big data and dashboards got a mention in both!), the audiences were quite different. For Insight, the large majority were from HE (Higher Education) libraries, followed by learning technologists, industry representatives, and HE decision-makers. In contrast, L@S consisted largely of academics, many from computing or technical backgrounds, with some industry researchers, including, as I was attending largely with my Talis hat on, me.

In a joint keynote at Insight, Paul Fieldman and Phil Richards the CEO and CIO of JISC, described the project to provide a learning analytics service [FR16,JI16] (including student app and, of course, dashboard) for UK institutions. As well as the practical benefits, they outlined a vision where the UK leads the way in educational big data for personalised learning.

In a joint keynote at Insight, Paul Fieldman and Phil Richards the CEO and CIO of JISC, described the project to provide a learning analytics service [FR16,JI16] (including student app and, of course, dashboard) for UK institutions. As well as the practical benefits, they outlined a vision where the UK leads the way in educational big data for personalised learning.

Given a long track record of education and educational technology research in the UK, the world-leading distance-learning university provision of the Open University, and recent initiatives both those outlined by JISC and FutureLearn (building on the OUs vast experience), this vision seems not unreasonable.

However, on the ground at Learning @ Scale, there was a very different picture; the vast majority of papers and attendees were from the US, an this despite the conference being held in Edinburgh.

To some extent this is as one might expect. While traditional distance learning, including the OU, has class sizes that for those in face-to-face institutions feel massive; these are dwarfed by those for MOOCs, which started in the US; and it is in the US where the main MOOC players (Coursera, udacity, edX) are based. edX alone had initial funding more than ten times that available to FutureLearn, so in sheer investment terms, the balance at L@S is representative.

However, Mike Sharples, long-term educational technology researcher and Academic Lead at FutureLearn, was one of the L@S keynotes [Sh16]. In his presentation it was clear that FutureLearn and UK MOOCs punch well above their weight, with retention statistics several times higher than US counterparts. While this may partly be due to topic areas, it is also a reflection of the development strategy. Mike outlined how empirically founded educational theory has driven the design of the FutureLearn platform, not least the importance of social learning. Perhaps then not surprisingly, one of the areas where FutureLearn substantially led over US counterparts was in social aspects of learning.

However, Mike Sharples, long-term educational technology researcher and Academic Lead at FutureLearn, was one of the L@S keynotes [Sh16]. In his presentation it was clear that FutureLearn and UK MOOCs punch well above their weight, with retention statistics several times higher than US counterparts. While this may partly be due to topic areas, it is also a reflection of the development strategy. Mike outlined how empirically founded educational theory has driven the design of the FutureLearn platform, not least the importance of social learning. Perhaps then not surprisingly, one of the areas where FutureLearn substantially led over US counterparts was in social aspects of learning.

So there are positive signs for UK research in these areas. While JISC has had its own austerity-driven funding problems, its role as trusted intermediary and active platform creator offers a voice and forum that few, if any, other countries posses. Similarly, while FutureLearn needs to be sustainable, so has to have a certain inward focus, it does seem to offer a wonderful potential resource for collaborative research. Furthermore the open education resource (OER) community seems strong in the UK.

The Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) [HC16,TH15] will bring its own problems, more about justifying student fee increases than education, potentially damaging education through yet more ill-informed political interference, and re-establishing class-based educational apartheid. However, it will certainly increase universities’ interest in education technology.

Set against this are challenges.

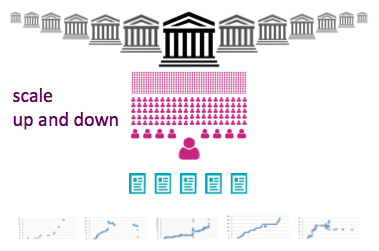

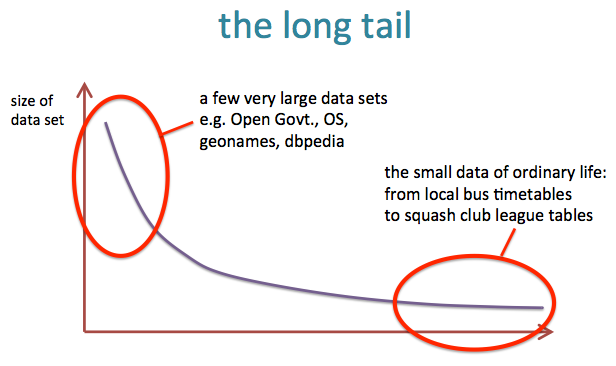

First was the topic of my own L@S work-in-progress paper – Challenge and Potential of Fine Grain, Cross-Institutional Learning Data [Dx16]. At Talis, we manage half a million reading lists, containing over 20 million resources, spread over more than 85 institutions including more than half of UK higher education. However, these institutions are all very different, and the half million courses each only may have only tens or low hundreds of students. That is very large scale in total volume, but highly heterogeneous. The JISC learning analytics repository will have exactly the same issues, and are far more difficult to deal with by machine learning or statistical analysis than the relatively homogeneous data from a single huge MOOC.

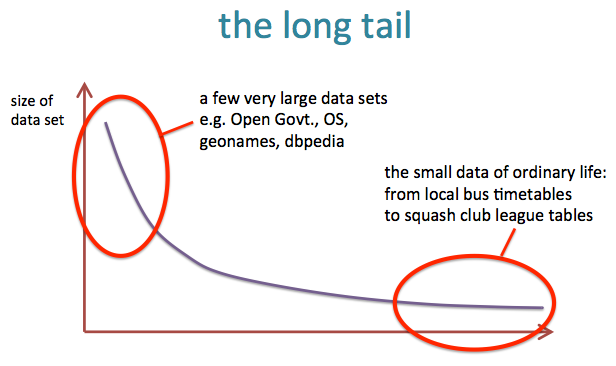

These issues of heterogeneous scale are not unique to education and ones that as a general information systems phenomena, I have been interested in for many years, and call the “long tail of small data” [Dx10,Dx15]. While this kind of data is more complex and difficult to deal with, this is of course a major research challenge, and potentially has greater long-term promise than the study of more homogeneous silos. I am finding this in my own work with musicologist [IC16,DC14], and is emerging as an issue in the natural sciences [Bo13,PC07].

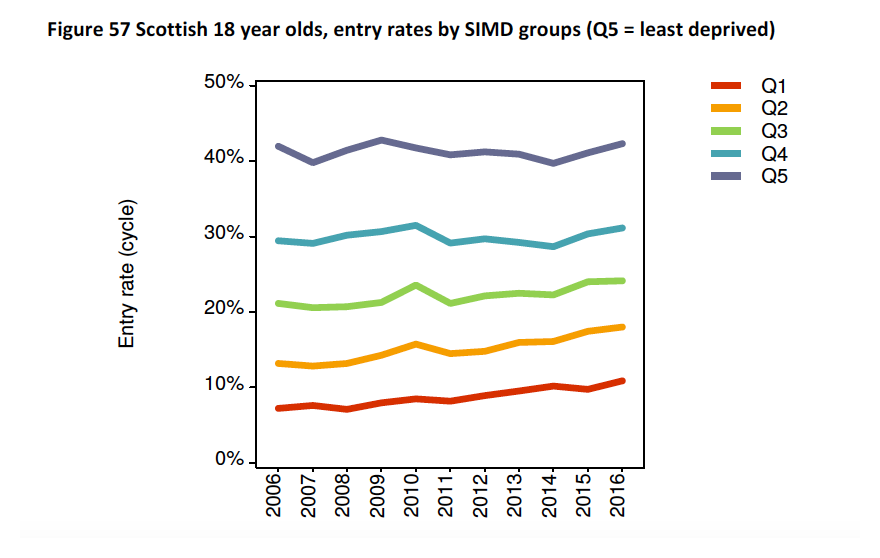

Another problem is REF, the UK ‘Research Excellence Framework’. My post-hoc analysis of the REF data revealed the enormous bias in the computing sub-panel against any form of applied and human-oriented work [Dx15b,Dx15c]. Of course, this is not a new issue, just that the available data has made this more obvious and undeniable. This affects my own core research area of human–computer interaction, but also, and probably much more substantially, learning technology research. Indeed, I think most learning technologists had already sussed this out well before REF2014 as there were very few papers submitted in this area to the computing panel. I assume most research on learning technology was submitted to the education panel.

To some extent it does not matter where research is submitted and assessed; however, while in theory the mapping between university departments and submitted units is fluid for REF, in practice submitting to ‘other’ panels is problematic making it difficult to write coherent narratives about the research environment. If learning technology research is not seen as REF-able in computing, computing departments will not recruit in these areas and discourage this kind of research. While my hope is that REF2020 will not re-iterate the mistakes of REF2014, there is no guarantee of this, and anyway the effects on institutional policy will already have been felt.

However, and happily, the kinds of research needed to make sense of this large-scale heterogeneous data may well prove more palatable to a computing REF panel than more traditional small-scale learning technology. It would be wonderful to see research collaborations between those with long-term experience and understanding of educational issues, with hard-core machine learning and statistical analysis – this is BIG DATA and challenging data. Indeed one of the few UK papers at L@S involved Pearson’s London-based data analysis department, and included automatic clustering, hidden Markov models, and regression analysis.

In short, while there are barriers in the UK, there is also great potential for exciting research that is both theoretically challenging and practically useful, bringing the insights available from large-scale educational data to help individual students and academics.

References

[Bo13] Christine L. Borgman. Big data and the long tail: Use and reuse of little data. Oxford eResearch Centre Seminar, 12th March 2013. http://works.bepress.com/borgman/269/

[Dx10] A. Dix (2010). In praise of inconsistency – the long tail of small data. Distinguished Alumnus Seminar, University of York, UK, 26th October 2011.

http://www.hcibook.com/alan/talks/York-Alumnus-2011-inconsistency/

[Dx15] A. Dix (2014/2015). The big story of small data. Talk at Open University, 11th November 2014; Oxford e-Research Centre, 10th July 2015; Mixed Reality Laboratory, Nottingham, 15th December 2015.

http://www.hcibook.com/alan/talks/OU-2014-big-story-small-data/

[DC14] Dix, A., Cowgill, R., Bashford, C., McVeigh, S. and Ridgewell, R. (2014). Authority and Judgement in the Digital Archive. In The 1st International Digital Libraries for Musicology workshop (DLfM 2014), ACM/IEEE Digital Libraries conference 2014, London 12th Sept. 2014. https://alandix.com/academic/papers/DLfM-2014/

[Dx15b] Alan Dix (2015/2016). REF2014 Citation Analysis. accessed 8/5/2016. https://alandix.com/ref2014/

[Dx15c] A. Dix (2015). Citations and Sub-Area Bias in the UK Research Assessment Process. In Workshop on Quantifying and Analysing Scholarly Communication on the Web (ASCW’15) at WebSci 2015 on June 30th in Oxford. http://ascw.know-center.tugraz.at/2015/05/26/dix-citations-and-sub-areas-bias-in-the-uk-research-assessment-process/

[Dx16] Alan Dix (2016). Challenge and Potential of Fine Grain, Cross-Institutional Learning Data. Learning at Scale 2016. ACM. https://alandix.com/academic/papers/LS2016/

[FR16] Paul Feldman and Phil Richards (2016). JISC – Helping the UK become the most advanced digital teaching and research nation in the world. Talis Insight Europe 2016. https://talis.com/2016/04/29/jisc-keynote-paul-feldman-phil-richards-talis-insight-europe-2016/

[HC16] The Teaching Excellence Framework: Assessing Quality in Higher Education. House of Commons, Business, Innovation and Skills Committee, Third Report of Session 2015–16. HC 572. 29 February 2016. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmselect/cmbis/572/572.pdf

[IC16] In Concert (2014-2016). accessed 8/5/2016 http://inconcert.datatodata.com

[JI16] Effective learning analytics. JISC, accessed 8/5/2016. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/rd/projects/effective-learning-analytics

[PC07] C. L. Palmer, M. H. Cragin, P. B. Heidorn and L.C. Smith. 2007. Data curation for the long tail of science: The Case of environmental sciences. 3rd International Digital Curation Conference, Washington, DC. https://apps.lis.illinois.edu/wiki/ download/attachments/32666/Palmer_DCC2007.pdf

[Sh16] Mike Sharples (2016). Effective Pedagogy at Scale, Social Learning and Citizen Inquiry (keynote). Learning at Scale 2016. ACM. http://learningatscale.acm.org/las2016/keynotes/#k2

[TH15] Teaching excellence framework (TEF): everything you need to know. Times Higher Education, August 4, 2015. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/teaching-excellence-framework-tef-everything-you-need-to-know