For many reasons, it is important for universities to re-open in the autumn, but it is also clear that this is a high-risk endeavour: bringing around 2% of the UK population together in close proximity for 10 to 12 weeks and then re-dispersing them at Christmas.

For many reasons, it is important for universities to re-open in the autumn, but it is also clear that this is a high-risk endeavour: bringing around 2% of the UK population together in close proximity for 10 to 12 weeks and then re-dispersing them at Christmas.

When I first estimated the actual size of the impact I was, to be honest, shocked; it was a turning point for me. With an academic hat on I can play with the numbers as an intellectual exercise, but we are talking about many, many thousands of lives at risk, the vast majority outside the university itself, with the communities around universities most at risk.

I have tried to think of easy, gentle and diplomatic ways of expressing this, but there are none; we seem in danger of creating killing zones around our places of learning.

At the very best, outbreaks will be detected early, and instead of massive deaths we will see substantial lockdowns in many university cities across the UK with the corresponding social and economic costs, which will create schisms between ‘town and gown’ that may poison civic relationships for years to come.

In the early months of the year many of us in the university sector watched with horror as we watched the Covid-19 numbers rising and could see where this would end. The eventual first ‘wave’ and its devastating death toll did not need sophisticated modelling to predict; in the intervening months it has played out precisely as expected. At that point the political will was clearly set and time was short; there was little we could do but shake our heads in despair and feel the pain of seeing our predictions become reality as the numbers grew, each number a person, each person a community.

Across the sector, many are worried about the implications of the return of students and staff in the autumn, but structurally the nature of the HE sector in the UK makes it near impossible even for individual universities to take sufficient steps to mitigate it, let alone individual academics.

Doing the sums

For some time, universities across the UK have been preparing for the re-opening, working out ways to reduce the risk. There has been a mathematical modelling working group trying to assess the impact of various measures, as well as much activity at individual institutions. It appears too that SAGE has highlighted that universities pose a potential risk [SN], but this seems to have gone cold and universities are coping as best they can with apparently no national plan. Universities UK have issued guidance to universities on what to do as they emerge from lockdown [UUKa], but it does not include an estimate of the scale of the problem.

As I said, the turning point for me came when I realised just how bad this could be. As with the early national growth pattern, it does not require complex mathematics to assess, within rough ranges, the potential impact; and even the most conservative estimates are terrifying.

We know from freshers’ flu that infections spread quickly amongst the student community. The social life is precisely why many students relocate to distant cities. Without strong measures to control student infections it is clear that Covid-19 will spread rapidly on campuses, leading to thousands of cases in each university. Students themselves are at low (though not zero) risk of dying or having serious complications from Covid-19, but if there is even small ‘leakage’ into the surrounding community (via university staff, transport systems, stay-at-home students or night life), then the impact is catastrophic.

For a mid-sized university of 20,000 students, let’s say only 1 in 20 become infected during the term; that is around 1,000 student cases. As a very conservative estimate, let’s assume just one community infection for every 10 infected students. If city bars are open this figure will almost certainly be much higher, but we’ll take a very low estimate. In this case, we are looking at 100 initial community cases.

Now 100 additional cases is already potentially enough to cause a handful of deaths, but we have got used to trading off social benefits against health costs; for any activity there is always a level of risk that we are prepared to accept.

However, the one bit of mathematics you do need to know is the way that a relatively small R number still leads to a substantial number of cases. For example, an R of 0.9 means for every initial infection the total number of infections is actually 10 times higher (in general 1/(1-R), see [Dx1]). When R is greater than 1 the effect is worse still, with the impact only limited when some additional societal measure kicks in, such as a vaccine or local lockdown.

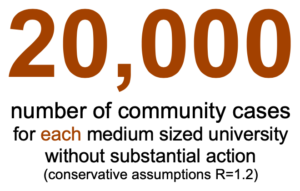

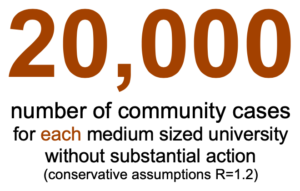

A relatively conservative estimate for R in the autumn is 1.5 [AMS]. For R =1.5, those initial 100 community cases magnify to over 10,000 within 5 weeks and more than 600,000 within 10 weeks. Even with the most optimistic winter rate of 1.2, those 100 initial community infections will give rise to 20,000 cases by the end of a term.

That is for a single university.

With a mortality rate of 1% and the most optimistic figures, this means that each university will cause hundreds of deaths. In other words, the universities in the UK will collectively create as many infections as the entire first wave. At even slightly less optimistic figures, the impact is even more devastating.

Why return at all?

Given the potential dangers, why are universities returning at all in the autumn instead of continuing with fully online provision?

In many areas of life there is a trade-off to be made between, on the one hand, the immediate Covid-19 health impacts and, on the other, a variety of issues: social, educational, economic, and also longer term and indirect mental and physical health implications. This is no less true when we consider the re-opening of universities.

Social implications: We know that the lockdown has caused a significant increase in mental health problems amongst young people, for a variety of reasons: the social isolation itself, pressures on families, general anxiety about the disease, and of course worries about future education and jobs. Some of the arguments are similar to those for schools except that universities do not provide a ‘child minding’ role. Crucially, for both schools and universities, we know that online education is least effective for those who are already most economically deprived, not least because of continued poor access to digital technology. We risk creating a missed generation and deepening existing fractures in civil society.

Furthermore, the critical role of university research has been evident during the Covid crisis, from the development of new treatments to practical use of infrastructure for rapid production of PPE. Ongoing, the initial wave has emphasised the need for more medical training. Of course, both education and research will also be critical for ‘post-Covid’ recovery.

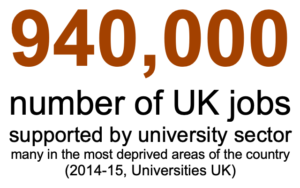

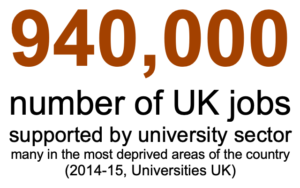

Economic situation: Across the UK, universities generate £95 billion in gross output and support nearly a million jobs (2014–2015 data, [UUKb]). Looking at Wales in particular, the HE sector “employs 17,300 full-time members of staff and spending by students and visitors supports an estimated 50,000 jobs across Wales”. At the same time the sector is particularly vulnerable to the effects of Covid-19 [HoC]. Universities across the UK were already financially straitened due to a combination of demographics and Brexit, leading to significant cost-cutting including job cuts [BBCa]. Covid-19 has intensified this; a Wales Fiscal Analysis briefing paper in May [WFA] suggests that Welsh universities may see a shortfall due to Covid-19 of between £100m and £140m. More recent estimates suggest that this may be understating the problem, if anything. Cardiff University alone is warning of a £168m fall in income [WO] and Sir Deian Hopkin, former Vice Chancellor of London South Bank and advisor to the Welsh Assembly, talks of a “perfect storm” in the university system [BBCb].

Government support has been minimal. The rules for Covid-19 furlough meant that universities were only able to take minimal advantage of the scheme. There has been some support in terms of general advice, reducing bureaucratic overheads and rescheduling payments to help university cashflow, but this has largely been within existing budgets, not new funding. The Welsh government has announced an FE/HE £50m support package with £27m targeting universities [WG], but this is small compared with predicted losses.

Universities across the UK have already cut casual teaching (the increase in zero-hour contracts has been a concern in HE for some years) and many have introduced voluntary severance schemes. At the same time the competition over UK students has intensified in a bid to make up for reduced international numbers. Yet one of the principal ways to attract students is to maximise the amount of in-person teaching.

What is being done

To some extent, as in so many areas, coronavirus has exposed the structural weaknesses that have been developing in the university sector for the past 30 years. Universities have been forced to compete constantly and are measured in terms of student experience above educational impact. Society as a whole has been bombarded with messages that focus on individual success and safety rather than communal goals, and most current students have grown up in this context. This focus has been very evident in the majority of Covid-19 information and reporting [Dx2].

Everything we do is set against this backdrop, which both fundamentally limits what universities are able to do individually, and at the same time makes them responsible. This is not to say that universities are not sharing good practice, both in top down efforts such as through Universities UK and direct contacts between senior management, and from the bottom up via person-to-person contacts and through subject-specific organisations such as CPHC.

Typically, universities are planning to retain some level of in-person teaching for small tutorials while completely or largely moving large-class activities such as lectures to online delivery, some live, some recorded. This will help to remove some student–student contact during teaching. Furthermore, many universities have discussed ways in which students could be formed into bubbles. At a large scale that could involve having rooms or buildings dedicated to a particular subject/year group for a day. At a finer scale it has been suggested that students could be grouped into social/study bubbles of around ten or a dozen who are housed together in student accommodation and are also grouped for study purposes.

My own modelling of student bubbles [Dx3] suggests that while reducing the level of transmission, the impact is rapidly eroded if the bubbles are at all porous. For example, if the small bubbles break and transmission hits whole year groups (80–200 students), the impact on outside communities becomes unacceptable. For students on campus the temptation to break these bubbles will be intense, both at an individual level and through bars and similar venues. For those living at home, the complexities are even greater, and crucially they are a primary vector into the local community.

Combined with, or instead of, social/study bubbles some universities are looking at track and trace. Some are developing their own solutions both in terms of apps and regular testing programmes, but more will use normal health systems. In Wales, for example, Public Health Wales regard university staff as a priority group for Covid-19 testing, although this is reactive (symptoms-based) rather than proactive (regular testing).

Dr Hans Kluge, the Europe regional director for the World Health Organization and others have warned that global surges across the world, including in Europe, are being driven by infections amongst younger people [BBCc]. He highlights the need to engage young people more in the science, a call that is reflected in a recent survey by the British Science Association which found that nine out of ten young people felt ignored by scientists and politicians [BSA].

As of 27th July, the UK Department for Education were “working to” two scenarios “Effective containment and testing” (reduce growth on campuses and reactive local lockdowns) and “On and off restrictions” (delaying all in-person teaching until January) [DfE]. Jim Dickinson has collated and analysed current advice and work at various government and advisory bodies including the DfE report above and SAGE, but so far there seems to be no public quantification of the risk [JD].

What can we do?

I think it is fair to say that the vast majority of high-level advice from national governments and pan-University bodies, and most individual university thinking, has been driven by safety concerns for students and staff rather than the potentially far more serious implications for society at large.

As with so many aspects of this crisis, the first step is to recognise there is a problem.

Within universities, acknowledge that the risk level will be far higher than in society at large because the case load will be far higher. How much higher will depend on mitigating measures, but whereas general population levels by the start of term may be as low as 1 in 5,000, the rate amongst students will be an order of magnitude higher, comparable with general levels during the peak of the ‘first wave’. This means that advice, particularly for at risk groups, which is targeted at national levels, needs to be re-thought within the university context. This means that advice that is targeted at national levels, particularly for at risk groups, needs to be re-thought within the university context. Individual vulnerable students are already worried [BBCd]. Chinese and Asian students seem more aware of the personal dangers and it is noticeable that both within the UK and in the US the universities with the greatest number of international students are more risk averse. University staff (academics, cleaners, security) will include more at risk individuals than the student body. It is hard to quantify, but the risk level will considerably higher than, say, a restaurant or pub, though of course lower than for front line medical staff. Even if it is ‘safe’ for vulnerable groups to come out of shielding in general society, it may not be safe in the context of the university. This will be difficult to manage: even if the university does not force vulnerable staff to return, the long-term culture of vocational commitment may make some people take unacceptable risks.

Outside the universities, local councils, national governments and communities need to be aware of the increased risks when the universities reopen, just as seaside towns have braced themselves for tourist surges post-lockdown. While SAGE has noted that universities may be an ‘amplifier’, the extent does not appear (at least publicly) to have been quantified. In Aberdeen recently a cluster around a small number of pubs has caused the whole city to return to lockdown, and it is hard to imagine that we won’t see similar incidents around universities. This may lead to hard decisions, as has been discussed, between opening schools or pubs [BBCe] – city centre bars may well need to be re-thought. Universities benefit communities substantially both economically and educationally. For individual universities alone the costs of, say, weekly testing of students and staff would be prohibitive, but when seen in terms of regional or national health protection these may well be worthwhile. Although this is a ‘for example’ it could well be critical given the likelihood of large numbers of asymptomatic student cases.

Educate students – this is of course what we do as universities! Covid-19 will be a live topic for every student, but they may well have many of the misconceptions that permeate popular discourse. Can we help them become more aware of the aspects that connect to their own disciplines and hence to become ambassadors of good practice amongst their peers? Within maths and computing we can look at models and data analysis, which could be used in other scientific areas where these are taught. Medicine is obvious and design and engineering students might have examples around PPE or ventilators. In architecture we can think about flows within buildings, ventilation, and design for hygiene (e.g. places to wash your hands in public spaces that aren’t inside a toilet!). In literature, there is pandemic fiction from Journal of the Plague Year to La Peste, and in economics we have examples of externalities (and if you leave externalities until a specialised final year option, rethink a 21st century economics syllabus!).

Time to act

On March 16, I posted on Facebook, “One week left to save the UK – and WE CAN DO IT.” Fortunately, we have more time now to ensure a safe university year but we need to act immediately to use that time effectively. We can do it.

References

[AMS] The Academy of Medical Sciences. Preparing for a challenging winter 2020-21. 14th July 2020. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/policy/policy-projects/coronavirus-preparing-for-challenges-this-winter

[BBCa] Cardiff University to cut 380 posts after £20m deficit. BBC News. 12th Feb 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-47205659

[BBCb] Coronavirus: Universities’ ‘perfect storm’ threatens future. Tomos Lewis BBC News. 7 August 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-53682774

[BBCc] WHO warns of rising cases among young in Europe. Lauren Turner, BBc New live reporting, 10:05am 29th July 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/live/world-53577222?pinned_post_locator=urn:asset:59cae0e7-5d3d-4e35-94ec-1895273ed016

[BBCd] Coronavirus: University life may ‘pose further risk’ to young shielders

Bethany Dawson. BBC News. 6th August 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/disability-53552077

[BBCe] Coronavirus: Pubs ‘may need to shut’ to allow schools to reopen. BBC News. 1st August 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-53621613

[BG] Colleges reverse course on reopening as pandemic continues. Deirdre Fernandes, Boston Globe, updated 2nd August 2020. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/08/02/metro/pandemic-continues-some-colleges-reverse-course-reopening/

[BSA] New survey results: Almost 9 in 10 young people feel scientists and politicians are leaving them out of the COVID-19 conversation. British Science Association. (undated) accessed 7/8/2020. https://www.britishscienceassociation.org/news/new-survey-results-almost-9-in-10-young-people-feel-scientists-and-politicians-are-leaving-them-out-of-the-covid-19-conversation

[DfE] DfE: Introduction to higher education settings in England, 1 July 2020 Paper by the Department for Education (DfE) for the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE). Original published 24th July 2020 (updated 27th July 2020). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dfe-introduction-to-higher-education-settings-in-england-1-july-2020

[Dx1] More than R – how we underestimate the impact of Covid-19 infection. . Dix (blog). 2nd August 2020 https://alandix.com/blog/2020/08/02/more-than-r-how-we-underestimate-the-impact-of-covid-19-infection/

[Dx2] Why pandemics and climate change are hard to understand, and can we help? A. Dix. North Lab Talks, 22nd April 2020 and Why It Matters, 30 April 2020 http://alandix.com/academic/talks/Covid-April-2020/

[Dx3] Covid-19 – Impact of a small number of large bubbles on University return. Working Paper. A. Dix. July 2020. http://alandix.com/academic/papers/Covid-bubbles-July-2020/

[HEFCW] COVID-19 impact on higher education providers: funding, regulation and reporting implications. HEFCW Circular, 4th May 2020 https://www.hefcw.ac.uk/documents/publications/circulars/circulars_2020/W20%2011HE%20COVID-19%20impact%20on%20higher%20education%20providers.pdf

[HoC] The Welsh economy and Covid-19: Interim Report. House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee. 16th July 2020. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/1972/documents/19146/default/

[JD] Universities get some SAGE advice on reopening campuses. Jim Dickinson, WonkHE, 25th July 2020. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/universities-get-some-sage-advice-on-reopening-campuses/

[SN] Coronavirus: University students could be ‘amplifiers’ for spreading COVID-19 around UK – SAGE. Alix Culbertson. Sky News. 24th July 2020. https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-university-students-could-be-amplifiers-for-spreading-covid-19-around-uk-sage-12035744

[UUKa] Principles and considerations: emerging from lockdown. Universities UK, June 2020. https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/principles-considerations-emerging-lockdown-uk-universities-june-2020.aspx

[UUKb] https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/economic-impact-universities-2014-15.aspx

[WFA] Covid-19 and the Higher Education Sector in Wales (Briefing Paper). Cian Siôn, Wales Fiscal Analysis, Cardiff University. 14th May 2020. https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2394361/Covid_FINAL.pdf

[WG] Over £50 million to support Welsh universities, colleges and students. Welsh Government press release. 22nd July 2020. https://gov.wales/over-50-million-support-welsh-universities-colleges-and-students

[WO] Cardiff University warns of possible job cuts as it faces £168m fall in income. Abbie Wightwick, Wales Online. 10th June 2020. https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/education/cardiff-university-job-losses-coronavirus-18393947

For many reasons, it is important for universities to re-open in the autumn, but it is also clear that this is a high-risk endeavour: bringing around 2% of the UK population together in close proximity for 10 to 12 weeks and then re-dispersing them at Christmas.

For many reasons, it is important for universities to re-open in the autumn, but it is also clear that this is a high-risk endeavour: bringing around 2% of the UK population together in close proximity for 10 to 12 weeks and then re-dispersing them at Christmas.