One of the wonders of the human mind is the way we can get inside one another’s skin; understand what each other is thinking, wanting, feeling. I’m thinking about this now because I’m reading The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition by , which is about the way understanding intentions enables cultural development. However, this also connects a hypotheses of my own from many years back, that our idea of self is a sort of ‘accident’ of being social beings. Also at the heart of Christmas is empathy, feeling for and with people, and the very notion of incarnation.

The central premise of Tomasello’s book is that:

(1) only cultural development can explain the remarkable development of the human race in the past 200 thousand years, as the changes we have seen are simply not explainable in terms of genetic evolution during that timescale

(2) the crucial genetic step that has fuelled this cultural explosion and the essential difference between humans and other animals is our ability to attribute intentionality to each other, to interpret others’ actions as being for some purpose.

Early on Tomasello describes this as:

“the ability of individual organisms to understand conspecifics as beings like themselves who have intentional and mental lives like their own” (p. 5, Tomasello’s emphasis)

While I agree with the broad argument, this specific statement is almost the opposite of the hypothesis, which I often talk about, concerning the origins of self-consciousness. In particular I suggest that the very concept of self may be an accident of sociality; we are aware of ourselves as intentional beings because we are aware of the intentionality of others.

By self-consciousness here I mean not feeling awkward in company, but the explicit awareness of oneself. This is not the same as consciousness, or simply being aware (one of the deepest mysteries), but more the declarative knowledge that one has intentions, actions, and thoughts.

My own argument runs like this.

In order to survive and prosper we need to be able to predict the actions of other creatures and our fellow humans. When chasing a rabbit it is useful to know that the rabbit will run away when it sees you approach, and that it will try to reach a nearby rabbit hole. Similarly, it is useful to know that one’s fellow hunters will attempt to cut off its escape route. These reactions during hunting could be purely instinctive, and probably are for many creatures such as pack animals, but with higher reasoning we can be more creative in terms of the strategies we use whether as hunter or prey; and this higher-order thinking is most effective when we can predict the actions of other creatures.

When the creature we are predicting is behaving largely instinctively, then our predictions can be similarly relatively simple. However, if the creature we wish to predict, a fellow human, is also able to employ these higher-order strategies, then we need to understand these in order to understand the other’s behaviour. In order to predict the behaviour of our fellow hunter, we need to take into account her understanding of the rabbit; and moreover, her understanding of ourself1.

That is, to understand others one has to think about oneself as if from the outside — self consciousness!

Returning to Tomasello, his argument is about mutual understanding as a means to learn through creatively emulating others, whereas my argument above is more about the instrumental understanding of others. Being able to understand motivation helps both. The instrumental case, I’ve already described – by understanding what motivations drove your behaviour I can more accurately predict under what circumstances you will behave similarly.

Tomasello’s developmental case is similar. If I am able to imitate others then I have additional behaviours that I can employ, but I still have to learn pretty much for myself when they are appropriate. However, if I know why someone else is behaving in the way that they do then I can instantly know when those behaviours are appropriate for me. When the reasons for behaviour are readily visible in the environment, for example, a sound in the bushes and everyone running, then no model of mind is necessary to learn the association between stimulus and imitated behaviour, but where the behaviour is the result of inner thoughts and drives then we need correspondingly more complex responses.

Tomasello (p. 99) argues that this is also essential for language development as we have to understand the perspective of others as we interpret or frame utterances.

One of the key aspects he identifies is precisely that language requires us to see ourselves “from the outside”, which is entirely consonant with my own argument that the notion of self is an accident of social intercourse. The issue is about which comes first phylogenetically, self or other. Tomasello (p. 70) notes that social theorists “from Vico and Dilthey to Cooley and Mead” stress that our understanding of others rests on parallels to our understanding of ourselves; I would simply add that the reason we have access to knowledge about ourselves may be precisely in order to understand others.

When discussing how children acquire a sense of self, he notes that research has shown that infants do not conceptualise or explicitly talk about themselves before they do about others. So, while it is not true that ontogeny inevitably recapitulates phylogeny, this is certainly suggestive evidence that self is at least no more primitive than other.

While my own and Tomasello’s position both rely on the understanding of the motives and intentions of others, there is also that much deeper sharing of feeling and emotion when we empathise with others. It maybe that empathy is more primitive than the awareness of our own or others intentions as we do not need to explicitly know what someone else is feeling, nor be able to articulate one’s own, in order to simply feel with them.

It is easy to see why it is useful to understand others emotions – if someone bigger than me is feeling upset and angry it may be better to steer clear. But the roots of empathy are less clear and obviously rooted in social cohesion and bonding; it is a feeling not just with others, but intrinsically for them.

This getting alongside others is exactly what Christmas is about “the word became human” (John 1:14, New Living Tr.) and Immanuel means precisely “God with us”; the ineffable becoming an infant.

Another term in the original Tomasello quote is “conspecifics”. We have a special understanding other creatures of the same species as ourselves. This is clearly important for imitation and learning, there is no sense in imitating the behaviour of creatures very different from ourselves, such as birds, as we may be physically not able to do the same things (can’t fly!) and anyway may not share the same kinds of motivations (e.g. making a place to lay eggs).

This works also within species, we need to learn the things that we are able to and need to perform and so it is those closest to us in terms of aspirations and abilities who are the most obvious to imitate. Yet it maybe those who are more different and more experienced who have most to offer. Diligent students understand this and step beyond the obvious peer group, but also the best teachers are able to see the world from the point of view of their students.

I read with fascination as Tomasello described many experiments of his own and others that look at small infants acquiring language. However, I also noted that the focus of them all was on the way in which the infant had to make sense of the parent or other adults words and gestures. In fact, it is also the parents who try to make sense of the inarticulate sounds and embryonic gestures of their child.

|

|

|

||

| look down | bend down | stoop down |

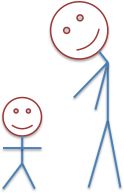

People differ in the way they interact with small children: some stand fully up and look down, some bend over the child from the waist, and some squat down or sit on a low chair so that they are the child’s level. It is the latter I always know are going to be the ‘naturals’ with children2.

To be a good teacher you sometimes need to become like a little child – Christmas.

- This is effectively a second order model of mind, First order model of mind is when we understanding that others have beliefs, motivations etc.; that is that they have mind. Second order is when we reason about their understanding of our minds, third order when we think about how they think about us thinking about them! One of Piaget’s critical development steps is when a child moves away form ego centrality to be able to understand other people’s different knowledge and physical point of view – first order model of mind. In autism this does not develop normally with corresponding social and other developmental impact. While most of us manage first order and second order model of mind without difficulty, but third order is more difficult and fourth and higher orders get hard to deal with except more analytically. This was wonderfully demonstrated by the Kursaal Flyers‘ 1976 one hit wonder which as the opening line: “Little does she know that I know that she knows that I know she’s two timing me.” (music at lastfm, lyrics at justsomelyrics) – fourth order model of mind! There was a video at the time that acted out the scene described in the song lyrics. [back]

- Of course, while people tend to interact naturally in one way or another, you can explicitly choose how to address a child.[back]