Across Europe the ultra-right wing raise again the ugly head of racism in scenes shockingly reminiscent of the late-1930s; while in America white supremacists throw stiff-armed salutes and shout “Heil Trump!” It has become so common that reporters no longer even remark on the swastikas daubed as part of neo-Nazi graffiti.

Yet against this we are beginning to see a counter movement, spoken in the soft language of liberalism, often well intentioned, but creating its own brand of facism. The extremes of the right become the means to label whole classes of people as ‘deplorable’, too ignorant, stupid or evil to be taken seriously, in just the same way as the Paris terrorist attacks or Cologne sexual assaults were used by the ultra-right to label all Muslims and migrants.

Hilary Clinton quickly recanted her “basket of depolarables”. However, it is shocking that this was said at all, especially by a politician who made a point of preparedness, in contrast to Trump’s off-the-cuff remarks. In a speech, which will have been past Democrat PR experts as well as Clinton herself, to label half of Trump supporters, at that stage possibly 20% of the US electorate, as ‘deplorable’ says something about the common assumptions that are taken for granted, and worrying because of that.

My concern has been growing for a long time, but I’m prompted to write now having read Pankaj Mishra‘s “Welcome to the age of anger” in the Guardian. Mishra’s article builds on previous work including Steven Levitt’s Freakonomics and the growing discourse on post-truth politics. He gives us a long and scholarly view from the Enlightenment, utopian visions of the 19th century, and models of economic self interest through to the fall of the Berlin Wall, the rise of Islamic extremism and ultimately Brexit and Trump.

The toxicity of debate in both the British EU Referendum and US Presidential Election is beyond doubt. In both debates both sides frequently showed a disregard for truth and taste, but there is little equivalence between the tenor of the Trump and Clinton campaign, and, in the UK, the Leave campaign’s flagrant disregard for fact made even Remain’s claims of imminent third world war seem tame.

Indeed, to call either debate a ‘debate’ is perhaps misleading as rancour, distrust and vitriol dominated both, so much so that Jo Cox viscous murder, even though the work of a single new-Nazi individual, was almost unsurprising in the growing paranoia.

Mishra tries to interpret the frightening tide of anger sweeping the world, which seems to stand in such sharp contrast to rational enlightened self-interest and the inevitable rise of western democracy, which was the dominant narrative of the second half of the 20th century. It is well argued, well sourced, the epitome of the very rationalism that it sees fading in the world.

It is not the argument itself that worries me, which is both illuminating and informing, but the tacit assumptions that lie behind it: the “age of anger” in the title itself and the belief throughout that those who disagree must be driven by crude emotions: angry, subject to malign ‘ressentiment‘, irrational … or to quote Lord Kerr (who to be fair was referring to ‘native Britains’ in general) just too “bloody stupid“.

Even the carefully chosen images portray the Leave campaigner and Trump supporter as almost bestial, rather than, say, the images of exultant joy at the announcement of the first Leave success in Sunderland, or even in the article’s own Trump campaign image, if you look from the central emotion filled face to those around.

The article does not condemn those that follow the “venomous campaign for Brexit” or the “rancorous Twitter troll”, instead they are treated, if not compassionately, impassionately: studied as you would a colony of ants or herd of wildebeest.

If those we disagree with are lesser beings, we can ignore them, not address their real concerns.

We would not treat them with the accidental cruelty that Dickens describes in pre-revolutionary Paris, but rather the paternalistic regard for the lower orders of pre-War Britain, or even the kindness of the more benign slave owner; folk not fully human, but worthy of care as you would a favourite dog.

Once we see our enemy as animal, or the populous as cattle, then, however well intentioned, there are few limits.

The 1930s should have taught us that.

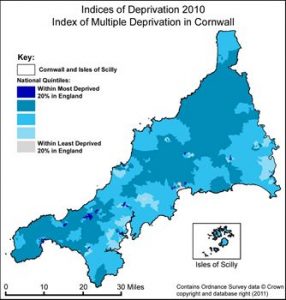

Reading Julia Rampen’s “11 things I feel more sorry about than Cornwall losing money after Brexit” in the New Statesman, I agree with all the groups she cites who are going to suffer the effects of Brexit, but did not vote for it.

Reading Julia Rampen’s “11 things I feel more sorry about than Cornwall losing money after Brexit” in the New Statesman, I agree with all the groups she cites who are going to suffer the effects of Brexit, but did not vote for it.