I have just finished reading “The Nature of Technology” (NoT) by W. Brian Arthur and some time ago read “The Evolution of Technology” (EoT) by George Basalla, both covering a similar topic, the way technology has developed from the earliest technology (stone axes and the wheel), to current digital technology. Indeed, I’m sure Arthur would have liked to call his book “The Evolution of Technology” if Basalla had not already taken that title!

We all live in a world dominated by technology and so the issue of how technology develops is critical to us all. Does technology ultimately serve human needs or does it have its own dynamics independent of us except maybe as cogs in its wheels? Is the arc of technology inevitable or does human creativity and invention drive it in new directions? Is the development of technology now similar (albeit a bit faster) than previous generations, or does digital technology fundamentally alter things?

Basalla was published in 1988, while Arthur is 2009, so Arthur has 20 years more to work on, not much compared to 2 million years for the stone axe and 5000 years for the wheel, but 20 years that has included the dot.com boom (and bust!), and the growth of the internet. In a footnote (NoT,p.17), Arthur describes Basalla as “the most complete theory to date“, although then does not appear to directly reference Basalla again in the text – maybe because they have different styles. Basalla (a historian of technology) offering a more descriptive narrative whilst Arthur (and engineer and economist) seeks a more analytically complete account. However I also suspect that Arthur discovered Basella’s work late and included a ‘token’ reference; he says that a “theory of technology — an “ology” of technology” is missing (NoT,p.14), but, however partial, Basella’s account cannot be seen as other than part of such a theory.

Both authors draw heavily, both explicitly and implicitly, on Darwinian analogies, but both also emphasise the differences between biological and technological evolution. Neither is happy with, what Basella calls the “heroic theory of invention” where “inventions emerge in a fully developed state from the minds of gifted inventors” (EoT,p.20). In both there are numerous case studies which refute these more ‘heroic’ accounts, for example Watts’ invention of the steam engine after seeing a kettle lid rattling on the fire, and show how these are always built on earlier technologies and knowledge. Arthur is more complete in eschewing explanations that depend on human ingenuity, and therein, to my mind, lies the weakness of his account. However, Arthur does take into account, as central mechanism, the accretion of technological complexity through the assembly of components, al but absent from Basella’s account — indeed in my notes as I read Basella I wrote “B is focused on components in isolation, forgets implication of combinations“.

I’ll describe the main arguments of each book, then look at what a more complete picture might look like.

(Note, very long post!)

Basella: the evolution of technology

Basella’s describes his theory of technological evolution in terms of four concepts:

- diversity of artefacts — acknowledging the wide variety both of different kinds of things, but also variations of the same thing — one example, dear to my heart, is his images of different kinds of hammers 🙂

- continuity of development — new artefacts are based on existing artefacts with small variations, there is rarely sudden change

- novelty — introduced by people and influenced by a wide variety of psychological, social and economic factors … not least playfulness!

- selection — winnowing out the less useful/efficient artefacts, and again influenced by a wide variety of human and technological factors

Basella sets himself apart both from earlier historians of technology (Gilfillan and Ogburn) who took an entirely continuous view of development and also the “myths of the heroic inventors” which saw technological change as dominated by discontinuous change.

He is a historian and his accounts of the development of artefacts are detailed and beautifully crafted. He takes great efforts to show how standard stories of heric invention, such as the steam engine, can be seen much more sensibly in terms of slower evolution. In the case of steam, the basic principles had given rise to Newcomen’s steam pump some 60 years prior to Watt’s first steam engine. However, whilst each of these stories emphasised the role of continuity, as I read them I was struck also by the role of human ingenuity. If Newcomen’s engine had been around since 1712 years, what made the development to a new and far more successful form take 60 years to develop? The answer is surely the ingenuity of James Watt. Newton said he saw further only because he stood on the shoulders of giants, and yet is no less a genius for that. Similaly the tales of invention seem to be both ones of continuity, but also often enabled by insights.

In fact, Basella does take this human role on board, building on Usher’s earlier work, which paced insight centrally in accounts of continuous change. This is particularly central in his account of the origins of novelty where he considers a rich set of factors that influence the creation of true novelty. This includes both individual factors such as playfulness and fantasy, and also social/cultural factors such as migration and the patent system. It is interesting however that when he turns to selection, it is lumpen factors that are dominant: economic, military, social and cultural. This brings to mind Margaret Bowden’s H-creativity and also Csikszentmihalyi’s cultural views of creativity — basically something is only truly creative (or maybe innovative) when it is recognised as such by society (discuss!).

Arthur: the nature of technology

Basella ends his book confessing that he is not happy with the account of novelty as provided from historical, psychological and social perspectives. Arthur’s single reference to Basella (endnote, NoT, p.17) picks up precisely this gap, quoting Basella’s “inability to account fully for the emergence of novel artefacts” (EoT,p.210). Arthur seeks to fill this gap in previous work by focusing on the way artefacts are made of components, novelty arising through the hierarchical organisation and reorganisation of these components, ultimately built upon natural phenomena. In language reminiscent of proponents of ‘computational thinking‘, Arthur talks of a technology being the “programming of phenomena for our purposes” (NoT,p.51). Although, not directly on this point, I should particularly liked Arthur’s quotation from Charles Babbage “I wish to God this calculation had been executed by steam” (NoT,p.74), but did wonder whether Arthur’s computational analogy for technology was as constrained by the current digital perspective as Babbage’s was by the age of steam.

Although I’m not entirely convinced at the completeness of hierarchical composition as an explanation, it is certainly a powerful mechanism. Indeed Arthur views this ‘combinatorial evolution’ as the key difference between biological and technological evolution. This assertion of the importance of components is supported by computer simulation studies as well as historical analysis. However, this is not the only key insight in Arthur’s work.

Arthur emphasises the role of what he calls ‘domains’, in his words a “constellation of technologies” forming a “mutually supporting set” (NoT,p.71). These are clusters of technologies/ideas/knowledge that share some common principle, such as ‘radio electronics’ or ‘steam power’. The importance of these are such that he asserts that “design in engineering begins by choosing a domain” and that the “domain forms a language” within which a particular design is an ‘utterance’. However, domains themselves evolve, spawned from existing domains or natural phenomena, maturing, and sometimes dying away (like steam power).

The mutual dependence of technology can lead to these domains suddenly developing very rapidly, and this is one of the key mechanisms to which Arthur attributes more revolutionary change in technology. Positive feedback effects are well studied in cybernetics and is one of the key mechanisms in chaos and catastrophe theory which became popularised in the late 1970s. However, Arthur is rare in fully appreciating the potential for these effects to give rise to sudden and apparently random changes. It is often assumed that evolutionary mechanisms give rise to ‘optimal’ or well-fitted results. In other areas too, you see what I have called the ‘fallacy of optimality’; for example, in cognitive psychology it is often assumed that given sufficient practice people will learn to do things ‘optimally’ in terms of mental and physical effort.

human creativity and ingenuity

Arthur’s account is clearly more advanced than the early more gradualists, but I feel that in pursuing the evolution of technology based on its own internal dynamics, he underplays the human element of the story. Arthur even goes so far as to describe technology using Maturna’s term autopoetic (NoT,p.170) — something that is self-(re)producing, self-sustaining … indeed, in some sense with a life of its own.

However, he struggles with the implications of this. If, technology responds to “its own needs” rather than human needs, “instead of fitting itself to the world, fits the world to itself” (NoT,p.214), does that mean we live with, or even within, a Frankenstein’s monster, that cares as little for the individuals of humanity as we do for our individual shedding skin cells? Because of positive feedback effects, technology is not deterministic; however, it is rudderless, cutting its own wake, not ours.

In fact, Arthur ends his book on a positive note:

“Where technology separates us from these (challenge, meaning, purpose, nature) it brings a type of death. But where it affirms these, it affirms life. It affirms our humanness.” (NoT,p.216)

However, there is nothing in his argument to admit any of this hope, it is more a forlorn hope against hope.

Maybe Arthur should have ended his account at its logical end. If we should expect nothing from technology, then maybe it is better to know it. I recall as a ten-year old child wondering just these same things about the arc of history: do individuals matter? Would the Third Reich have grown anyway without Hitler and Britain survived without Churchill? Did I have any place in shaping the world in which I was to live? Many years later as I began to read philosophy, I discovered these were questions that had been asked before, with opposing views, but no definitive empirical answer.

In fact, for technological development, just as for political development, things are probably far more mixed, and reconciling Basella and Arthur’s accounts might suggest that there is space both for Arthur’s hope and human input into technological evolution.

Recall there were two main places where Basella placed human input (individual and special/cultural): novelty and selection.

The crucial role of selection in Darwinian theory is evident in its eponymous role: “Natural Selection”. In Darwinian accounts, this is driven by the breeding success of individuals in their niche, and certainly the internal dynamics of technology (efficiency, reliability, cost effectiveness, etc.) are one aspect of technological selection. However, as Basella describes in greater detail, there are many human aspects to this as well from the multiple individual consumer choices within a free market to government legislation, for example regulating genome research or establishing emissions limits for cars. This suggest a relationship with technology les like that with an independently evolving wild beast and more like that of the farmer artificially selecting the best specimens.

Returning to the issue of novelty. As I’ve noted even Basella seems to underplay human ingenuity in the stories of particular technologies, and Arthur even more so. Arthur attempts account for “the appearance of radically novel technologies” (NoT,p.17) though composition of components.

One example of this is the ‘invention’ of the cyclotron by Ernest Lawrence (Not,p.114). Lawrence knew of two pieces of previous work: (i) Rolf Wideröe’s idea to accelerate particles using AC current down a series of (very) long tubes, and (ii) the fact that magnetic fields can make charged particles swing round in circles. He put the two together and thereby made the cyclotron, AC currents sending particles ever faster round a circular tube. Lawrence’s first cyclotron was just a few feet across; now, in CERN and elsewhere, they are many miles in diameter, but the principle is the same.

Arthur’s take-home message from this is that the cyclotron did not spring ready-formed and whole from Lawrence’s imagination, like Athena from Zeus’ head. Instead, it was the composition of existing parts. However, the way in which these individual concepts or components fitted together was far from obvious. In many of the case studies the component technology or basic natural phenomena had been around and understood for many years before they were linked together. In each case study it seems to be the vital key in putting together the disparate elements is the human one — heroic inventors after all 🙂

Some aspects of this invention not specifically linked to composition: experimentation and trial-and-error, which effectively try out things in the lab rather than in the market place; the inventor’s imagination of fresh possibilities and their likely success, effectively trail-and-error in the head; and certainly the body of knowledge (the domains in Arthur’s terms) on which the inventor can draw.

However, the focus on components and composition does offer additional understanding of how these ‘breakthroughs’ take place. Randomly mixing components is unlikely to yield effective solutions. Human inventors’ understanding of the existing component technologies allows them to spot potentially viable combinations and perhaps even more important their ability to analyse the problems that arise allow them to ‘fix’ the design.

In my own work in creativity I often talk about crocophants, the fact that arbitrarily putting two things together, even if each is good in its own right, is unlikely to lead to a good combination. However, by deeply understanding each, and why they fit their respective environments, one is able to intelligently combine things to create novelty.

Darwinism and technology

Both Arthur and Basalla are looking for modified version of Darwinism to understand technological evolution. For Arthur it is the way in which technology builds upon components with ‘combinatorial evolution’. While pointing to examples in biology he remarks that “the creation of these larger combined structures is rarer in biological evolution — much rarer — than in technological evolution” (NoT,p.188). Strangely, it is precisely the power of sexual reproduction over simpler mutation, that it allows the ‘construction’ and ‘swopping’ of components; this is why artificial evolutionary algorithms often outperform simple mutation (a form of stochastic hill-climbing algorithm, itself usually better than deterministic hill climbing). However, technological component combination is not the same as biological components.

A core ‘problem’ for biological evolution is the complexity of the genotype–phenotype mapping. Indeed in “The Selfish Gene” Dawkins attacks Lamarckism precisely on the grounds that the mapping is impossibly complex hence cannot be inverted. In fact, Dawkins arguments would also ‘disprove’ Darwinian natural selection as it also depends on the mapping not being too complex. If the mapping between genotype–phenotype were as complex as Dawkins suggested, then small changes to genotypes as gene patterns would lead to arbitrary phenotypes and so fitness of parents would not be a predictor of fitness of offspring. In fact while not simple to invert (as is necessary for Lamarckian inheritance) the mapping is simple enough for natural selection to work!

One of the complexities of the genotype–phenotype mapping in biology is that the genotype (our chromosomes) is far simpler (less information) than our phenotype (body shape, abilities etc.). Also the complexity of the production mechanism (a mothers womb) is no more complex than the final product (the baby). In contrast for technology the genotype (plans, specifications, models, sketches), is of comparable complexity to the final product. Furthermore the production means (factory, workshop) is often far more complex than the finished item (but not always, the skilled woodsman can make a huge variety of things using a simple machete, and there is interesting work on self-fabricating machines).

The complexity of the biological mapping is particularly problematic for the kind of combinatorial evolution that Arthur argues is so important for technological development. In the world of technology, the schematic of a component is a component of the schematic of the whole — hierarchies of organisation are largely preserved between phenotype and geneotype. In contrast, genes that code for finger length are also likely to affect to length, and maybe other characteristics as well.

As noted sexual reproduction does help to some extent as chromosome crossovers mean that some combinations of genes tend to be preserved through breeding, so ‘parts’ of the whole can develop and then be passed together to future generations. If genes are on different chromosomes, this process is a bit hit-and-miss, but there is evidence that genes that code for functionally related things (and therefore good to breed together), end up close on the same chromosome, hence more likely to be passed as a unit.

In contrast, there is little hit-and-miss about technological ‘breeding’ if you want component A from machine X and component B from machine Y, you just take the relevant parts of the plans and put them together.

Of course, getting component A and component B to work together is anther matter, typically some sort of adaptation or interfacing is needed. In biological evolution this is extremely problematic, as Arthur says “the structures of genetic evolution” mean that each step “must produce something viable” NoT,p.188). In contrast, the ability to ‘fix’ the details composition in technology means that combinations that are initially not viable, can become so.

However, as noted at the end of the last section, this is due not just to the nature of technology, but also human ingenuity.

The crucial difference between biology and technology is human design.

technological context and infrastructure

A factor that seems to be weak or missing in both Basella and Arthur’s theories, is the role of infrastructure and general technological and environmental context. This is highlighted by the development of the wheel.

The wheel and fire are often regarded as core human technologies, but whereas the fire is near universal (indeed predates modern humans), the wheel was only developed in some cultures. It has long annoyed me when the fact that South American civilisations did not develop the wheel is seen as some kind of lack or failure of the civilisation. It has always seemed evident that the wheel was not developed everywhere simply because it is not always useful.

I was wonderful therefore to read Basella’s detailed case study of the wheel (EoT,p.7–11) where he backs up what for me had always been a hunch, with hard evidence. I was aware that the Aztecs had wheeled toys even though they never used wheels for transport. Basella quite sensibly points out that this is reasonable given the terrain and the lack of suitable draught animals. He also notes that between 300–700 AD wheels were abandoned in the Near East and North Africa — wheels are great if you have flat hard natural surfaces, or roads, but not so useful on steep broken hillsides, thick forest, or soft sandy deserts.

I was wonderful therefore to read Basella’s detailed case study of the wheel (EoT,p.7–11) where he backs up what for me had always been a hunch, with hard evidence. I was aware that the Aztecs had wheeled toys even though they never used wheels for transport. Basella quite sensibly points out that this is reasonable given the terrain and the lack of suitable draught animals. He also notes that between 300–700 AD wheels were abandoned in the Near East and North Africa — wheels are great if you have flat hard natural surfaces, or roads, but not so useful on steep broken hillsides, thick forest, or soft sandy deserts.

In some ways these combinations: wheels and roads, trains and rails, electrical goods and electricity generation can be seen as a form of domain in Arthur’s sense, a “mutually supporting set” of technologies (NoT,p.71), indeed he does talk abut the “canal world” (NoT,p82). However, he is clearly thinking more about the component technologies that make up a new artefact, and less about the set of technologies that need to surround new technology it make it viable.

The mutual interdependence of infrastructure and related artefacts forms another positive feedback loop. In fact, in his discussion of ‘lock-in’, Arthur does talk about the importance of “surrounding structures and organisations”, as a constraint often blocking novel technology, and the way some technologies are only possible because of others (e.g. complex financial derivatives only possible because of computation). However, the best example is Basalla’s description of the of the development of the railroad vs. canal in the American Mid-West (EoT,p.195–197). This is often seen as simply the result of the superiority of the railway, but in the 1960s, Robert Fogel, a historian, made a detailed economic comparison and found that there was no clear financial advantage; it is just that once one began to become dominant the positive feedback effects made it the sole winner.

Arthur’s compositional approach focuses particularly on hierarchical composition, but these infrastructures often cut across components: the hydraulics in a plane, electrical system in a car, or Facebook ‘Open Graph’. And of course one of the additional complexities of biology is that we have many such infrastructure systems in our own bodies blood stream, nervous system, food and waste management.

It is interesting that the growth of the web was possible by a technological context of the existing internet and home PC sales (which initially were not about internet use, even though now this is often the major reason for buying computational devices). However, maybe the key technological context for the modern web is the credit card, it is online payments and shopping, or the potential for them, that has financed the spectacular growth of the area. There would be no web without Berners Lee, but equally without Barclay Card.

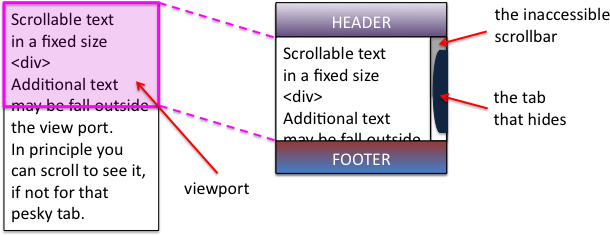

I was reading a quite disturbing article on a

I was reading a quite disturbing article on a

One of my birthday presents was Steven Mithin’s “

One of my birthday presents was Steven Mithin’s “