Had a great day on Saturday at the at the Web Art/Science Camp (twitter: #webartsci , lanyrd: web-art-science-camp). It was the first event that I went to primarily with my Talis hat on and first Web Science event, so very pleased that Clare Hooper told me about it during the DESIRE Summer School.

The event started on Friday night with a lovely meal in the restaurant at the British Museum. The museum was partially closed in the evening, but in the open galleries Rosetta Stone, Elgin Marbles and a couple of enormous totem poles all very impressive. … and I notice the BM’s website when it describes the Parthenon Sculptures does not waste the opportunity to tell us why they should not be returned to Greece!

I was fascinated too by images of the “Treasury of Atreus” (which is actually a Greek tomb and also known as the Tomb of Agamemnon. The tomb has a corbelled arch (triangular stepped stones, as visible in the photo) in order to relieve load on the lintel. However, whilst the corbelled arch was an important technological innovation, the aesthetics of the time meant they covered up the triangular opening with thin slabs of fascia stone and made it look as though lintel was actually supporting the wall above — rather like modern concrete buildings with decorative classical columns.

how web killed the hypertext star

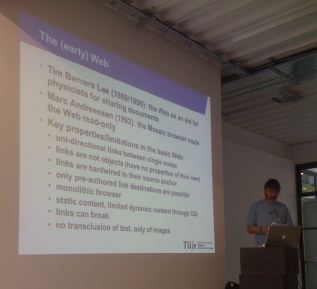

On Saturday, the camp proper started with Paul de Bra from TU/e giving a sort of retrospective on pre-web hypertext research and whether there is any need for hypertext research anymore. The talk brought out several of the issues that have worried me also for some time; so many of the lessons of the early hypertext lost in the web1.

For me one of the most significant issues is external linkage. HTML embeds links in the document using <a> anchor tags, so that only the links that the author has thought of can be present (and only one link per anchor). In contrast, mature pre-web hypertext systems, such as Microcosm2, specified links eternally to the document, so that third parties could add annotation and links. I had a few great chats about this with one of the Southampton Web Science DTC students; in particular, about whether Google or Wikipedia effectively provide all the external links one needs.

Paul’s brief history of hypertext started, predictably, with Vannevar Bush‘s “As We May Think” and Memex; however he pointed out that Bush’s vision was based on associative connections (like the human mind) and trails (a form of narrative), not pairwise hypertext links. The latter reminded me of Nick Hammond’s bus tour metaphor for guided educational hypertext in the 1980s — occasionally since I have seen things a little like this, and indeed narrative was an issue that arose in different guises throughout the day.

While Bush’s trails are at least related to the links of later hypertext and the web, the idea of associative connections seem to have been virtually forgotten. More recently in the web however, IR (information retrieval) based approaches for page suggestions like Alexa and content-based social networking have elements of associative linking as does the use of spreading activation in web contexts3

It was of course Nelson who coined the term hypertext, but Paul reminded us that Ted Nelson’s vision of hypertext in Xanadu is far richer than the current web. As well as external linkage (and indeed more complex forms in his ZigZag structures, a form of faceted navigation.), Xanadu’s linking was often in the form of transclusions pieces of one document appearing, quoted, in another. Nelson was particularly keen on having only one copy of anything, hence the transclusion is not so much a copy as a reference to a portion. The idea of having exactly one copy seems a bit of computing obsession, and in non-technical writing it is common to have quotations that are in some way edited (elision, emphasis), but the core thing to me seems to be the fact that the target of a link as well as the source need not be the whole document, but some fragment.

Over a period 30 years hypertext developed and started to mature … until in the early 1990s came the web and so much of hypertext died with its birth … I guess a bit like the way Java all but stiltified programming languages. Paul had a lovely list of bad things about the web compared with (1990s) state of the art hypertext:

Key properties/limitations in the basic Web:

- uni-directional links between single nodes

- links are not objects (have no properties of their own)

- links are hardwired to their source anchor

- only pre-authored link destinations are possible

- monolithic browser

- static content, limited dynamic content through CGI

- links can break

- no transclusion of text, only of images

Note that 1, 3 and 4 are all connected with the way that HTML embeds links in pages rather than adopting some form of external linkage. However, 2 is also interesting; the fact that links are not ‘first class objects’. This has been preserved in the semantic web where an RDF triple is not itself easily referenced (except by complex ‘reification’) and so it is hard to add information about relationships such as provenance.

Of course, this same simplicity (or even that it was simplistic) that reduced the expressivity of HTML compared with earlier hypertext is also the reasons for its success compared with earlier more heavy weight and usually centralised solutions.

However, Paul went on to describe how many of the features that were lost have re-emerged in plugins, server enhancements (this made me think of systems such as zLinks, which start to add an element of external linkage). I wasn’t totally convinced as these features are still largely in research prototypes and not entered the mainstream, but it made a good end to the story!

demos and documentation

There was a demo session as well as some short demos as part of talks. Lots’s of interesting ideas. One that particularly caught my eye (although not incredibly webby) was Ana Nelson‘s documentation generator “dexy” (not to be confused with doxygen, another documentation generator). Dexy allows you to include code and output, including screen shots, in documentation (LaTeX, HTML, even Word if you work a little) and live updates the documentation as the code updates (at least updates the code and output, you need to change the words!). It seems to be both a test harness and multi-version documentation compiler all in one!

I recall that many years ago, while he was still at York, Harold Thimbleby was doing something a little similar when he was working on his C version of Knuth’s WEB literate programming system. Ana’s system is language neutral and takes advantage of recent developments, in particular the use of VMs to be able to test install scripts and to be sure to run code in a consistent environments. Also it can use browser automation for web docs — very cool 🙂

Relating back to Paul’s keynote this is exactly an example of Nelson’s transclusion — the code and outputs included in the document but still tied to their original source.

And on this same theme I demoed Snip!t as an example of both:

- attempting to bookmark parts of web pages, a form of transclusion

- using data detectors a form of external linkage

Another talk/demo also showed how Compendium could be used to annotate video (in the talk regarding fashion design) and build rationale around … yet another example of external linkage in action.

… and when looking after the event at some of Weigang Wang‘s work on collaborative hypermedia it was pleasing to see that it uses a theoretical framework for shared understanding in collaboratuve hypermedia that builds upon my own CSCW framework from the early 1990s 🙂

sessions: narrative, creativity and the absurd

Impossible to capture in a few words, but one session included different talks and discussion about the relation of narrative and various forms of web experiences — including a talk on the cognitive psychology of the Kafkaesque. Also discussion of creativity with Nathan live recording in IBIS!

what is web science

I guess inevitably in a new area there was some discussion about “what is web science” and even “is web science a discipline”. I recall similar discussions about the nature of HCI 25 years ago and not entirely resolved today … and, as an artist who was there reminded us, they still struggle with “what is art?”!

Whether or not there is a well defined discipline of ‘web science’, the web definitely throws up new issues for many disciplines including new challenges for computing in terms of scale, and new opportunities for the social sciences in terms of intrinsically documented social interactions. One of the themes that recurred to distinguish web science from simply web technology is the human element — joy to my ears of course as a HCI man, but I think maybe not the whole story.

Certainly the gathering of people from different backgrounds in a sort of disciplinary bohemia is exciting whether or not it has a definition.

- see also “Names, URIs and why the web discards 50 years of computing experience“[back]

- Wendy Hall, Hugh Davis and Gerard Hutchings, “Rethinking Hypermedia:: The Microcosm Approach, Springer, 1996.[back]

- Spreading activation is used by a number of people, some of my own work with others at Athens, Rome and Talis is reported in “Ontologies and the Brain: Using Spreading Activation through Ontologies to Support Personal Interaction” and “Spreading Activation Over Ontology-Based Resources: From Personal Context To Web Scale Reasoning“.[back]