A record number of students have been heading to universities over the last few weeks. They will still face Covid-restriction, however, happily the situation will be nothing like last year.

Last year I had my own concerns early on, and in retrospect it is easier to assess just how bad things were. Combining SAGE’s Sept 2020 estimates of the impact with actual Covid mortality would suggest that during 2020-2021 there was an additional death for every 50-100 university students educated. There are arguments to reduce this figure somewhat; however, it is still clear that society at large paid heavily to enable education to continue.

Happily, this year vaccination has vastly reduced mortality, albeit set against very high case numbers. Although things will be more ‘normal’ this year, as a sector, we are still clearly deeply indebted to the rest of society and need to do all we can to minimise further impact.

The data – how bad was it?

Early in the summer of 2020 I estimated that the potential impact of autumn University return would be to at least double the number of Covid cases unless major action was taken to mitigate the risks. Based on figures for the first wave and projections for 2020-2021 winter, I put the figure at around 50,000 deaths.

At the time this was derided as heavily pessimistic, but of course within months SAGE modelling estimates came out with far higher figures. SAGE’s “Summary of the effectiveness and harms of different non-pharmaceutical interventions, 21 September 2020” estimated that without substantial mitigation, university return in 2020 would lead to an increase in R of between 0.2 and 0.5, which corresponds to not just double, but between eight to sixty times as many cases over the first term.

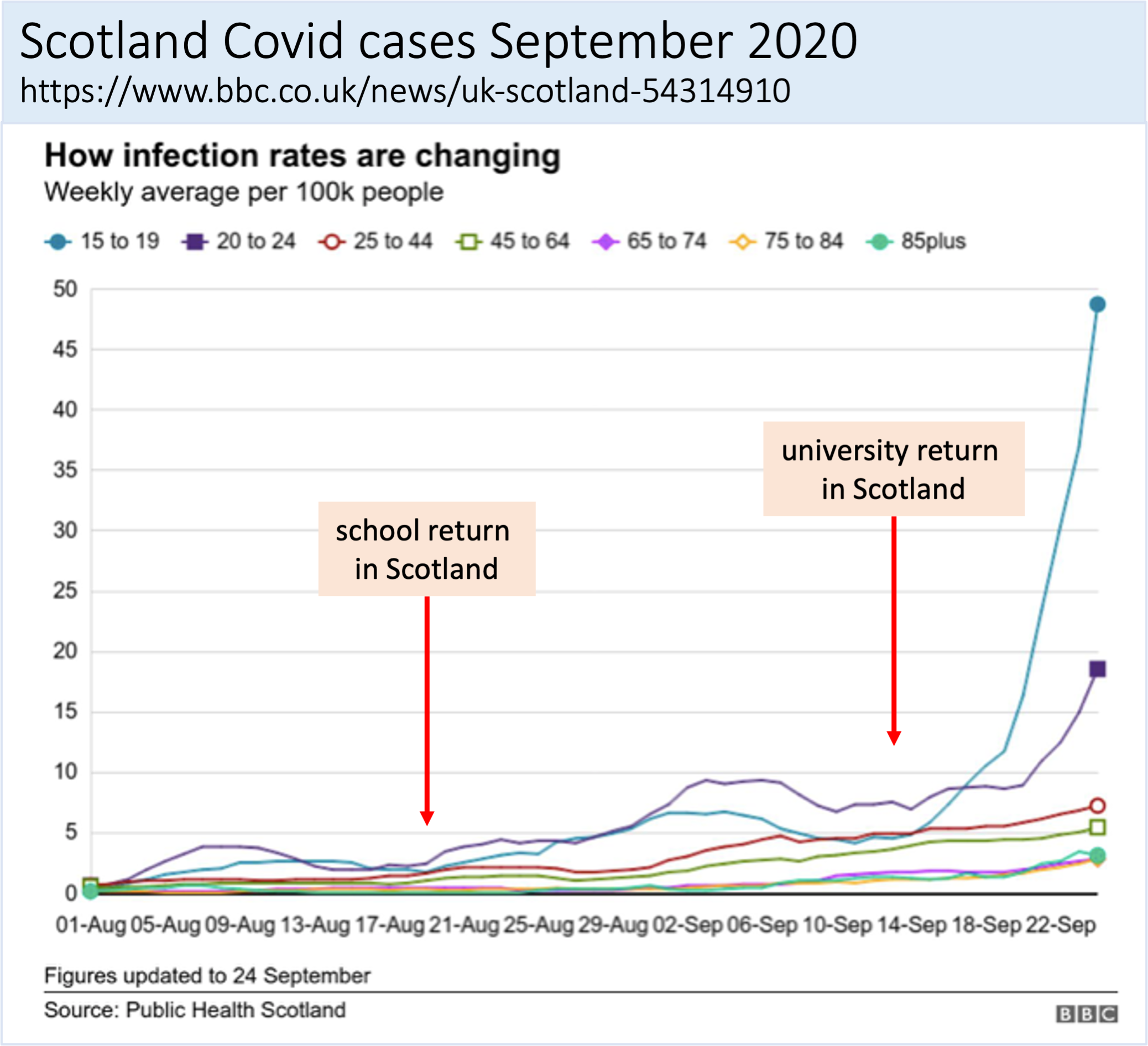

This was all based on modelling, but the impact was evident in actual case data as Universities returned. This was particularly clear in Scotland as universities returned in mid-September where there was an almost instant doubling of infections in the university age group, which then fed into other cohorts over the succeeding weeks.

As well as more local measures, the Universities Scotland issued guidance for the weekend of 25-27 Sept 2020 asking students to avoid socialising outside their households and avoiding bars and other such venues.

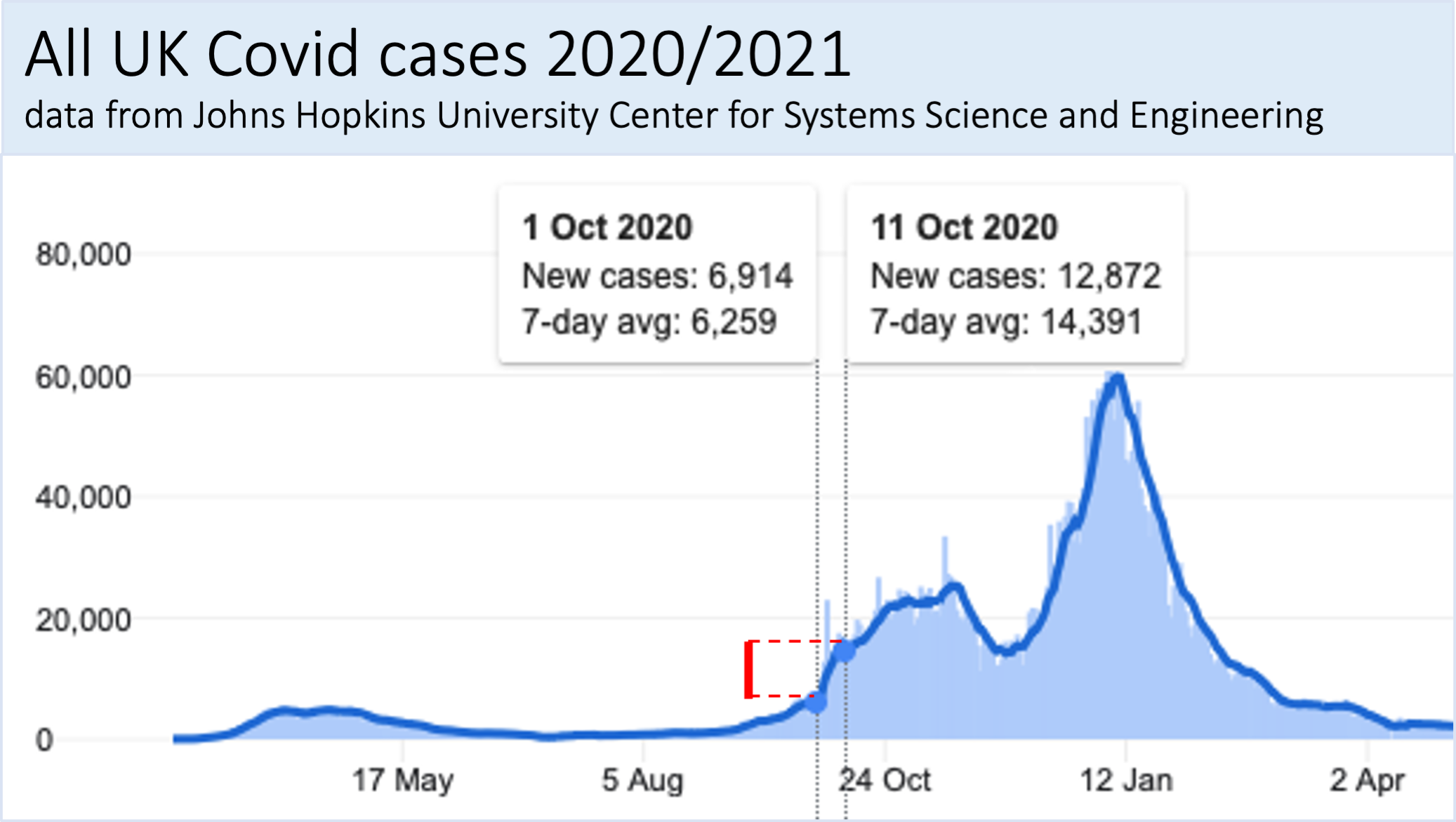

In the rest of the UK the data was a little less clear as university return dates are more staggered, but there was a clear step change at the beginning of October 2020.

In Newcastle the local newspaper analysed national data and found that areas with high student density had Covid rates five times higher than areas with few students. More anecdotally, we will all remember the images of students’ messages on their windows as halls went into effective lock-in, and the (rapidly removed) fencing around Manchester halls of residence.

This initial surge was due to the combination of simply lots of people coming together and establishing new contact networks, a known Covid risk, and the more obvious effect of start-of-term parties and ‘freshers week’ high spirits.

It is far harder to assess more long-term impacts during the year, as this simply added to the general societal growth. Modelling can be used to attempt to disentangle these effects, but it is difficult to definitively separate effects of coupled dynamic systems except during periods of sudden change. There were noticeable end-of-year spikes in student areas of Leeds reported in June, but that, like the year start, was more about end of term parties, not the general effect of increased contact networks.

Mitigations – it could have been worse

SAGE’s figures, like my own, were for University return without mitigations. and they suggested potential actions to reduce the impact, some of which were headed.

Every university made very strong efforts to reduce spread within teaching environments, whilst still offering levels of in-person activities, but it was, and still is, the social side of student life that was expected to be most problematic.

Anticipating the mixing during Freshers Week, my own University and I know many others, created outdoor bars and activities in order to create spaces that were safer and less likely to lead to cross infection. This was effective in that the majority of traced ‘superspreader’-style outbreaks seemed to be related to off-campus parties or events.

Students also took matters into their own hands. For every highly publicised case of wild parties and ignoring of Covid rules, I heard other less highly published accounts of students effectively permanently isolating themselves in their rooms. I also know of universities where courses that started off in hybrid mode with a mix of in-person and remote activities ended up abandoning the in-person elements as students effectively voted with their feet. I think this was principally the case for universities with a large number of local students, but also some students simply returned home and completed their studies remotely.

But students are young, so not at risk

One of the difficulties when thinking both about universities and schools, is that Covid is not particularly dangerous for those in their teens and twenties. This is not to say no risk for pupils and students, especially for anyone with other health problems. There is of course more risk for academics and teachers, and even more other staff such as cleaners, security and catering, who typically have older demographics than teachers and academics, but still the risk for working age adults was always smaller.

The biggest problem was, and still is, the spread into the community as a whole. The Scottish data for last autumn showed this indeed did happen within weeks. This is partly due to out-of-house contacts such as buses and shops, and partly due to home visits (for away-from-home students) and local students living at home.

These contacts then seed others and these indirect contacts, contacts of contacts, etc. far exceed the number of initial cases, and furthermore ended up spread over all demographics of society including the most vulnerable. When the disease is near static (R ~ 0.9–1.1) this leads to around 10 additional cases for each initial case over a 2-3 month window, higher during times of higher growth. While universities actively published the number of actual student and staff cases, these were the relatively safe tip of a far more deadly iceberg.

Last year, before the vaccine and new variants, these knock-on infections meant that each preventable infection would have a one in ten chance of causing an eventual death (see “More than R – how we underestimate the impact of Covid-19 infection” for the details of this figure). At our current mid-vaccine stage, but with delta, the figure is about one in fifty – still far higher than any of the common risks we impose upon one another such as car driving, second-hand smoking or general pollution.

What about variants?

While the data suggests that at least half of the cases during the autumn of 2020 were due to university returns, the original Covid variant was overtaken first of all by alpha variant and then by delta variant. There is thus an argument that only the deaths due to the original variant be counted, that is perhaps 10,000 deaths rather than 40-50,000.

For the delta variant this is undoubtedly the case; it quickly overcame the original variant and so the number of cases before the delta variant emerged are largely irrelevant to those that came after. However, delta only emerged in the UK as the second wave decayed and after the majority of deaths, so it makes little difference to the overall tally.

Alpha is more complex. Nearly all second wave deaths were due to alpha, and these constitute the larger part of winter 2020–2021 Covid deaths.

It is almost certain that alpha developed in the UK. It could be that it developed in a person who would have been infected anyway irrespective of the universities. If so then only around a half of pre-Christmas deaths should be attributed to the universities. However, if it developed as a mutation in someone who would not have been otherwise infected, not only all of the alpha variant UK deaths, but also all alpha variant deaths worldwide would land at our doorstep.

There is no way of knowing, but the odds as to which of these is the case run exactly with the proportion of cases due to the universities, so the best estimate is still to count that proportion of UK deaths and in principle a proportion of worldwide alpha-variant deaths also, but I don’t have the heart to calculate that figure, only knowing it is a lot, lot higher.

Why not blame schools?

Arguably, it is unfair to pin the increase entirely on the universities.

According to the SAGE estimates in Sept 2020, the two largest potential drivers of Covid were schools and universities. Each were expected to lead to increases in R of 0.2 to 0.5. That is, if universities had returned but schools not reopened, while the universities would have still doubled the number of cases, this would have doubling a smaller number. Given both schools and universities have similar figures then maybe it would be more fair to divide the combined impact between them, leading to maybe 3/8 of cases being assigned to each rather than half the cases to the universities.

This is a tenable argument, and indeed it is always hard to apportion blame or cost when faced with multiple causes that lead to non-linear effects.

Personally, I discount this. First because it doesn’t make so much difference, 3/8 of a big number is still very large. Second there were far stronger arguments for reopening schools: (i) because being more local to start with it was easier to mitigate their impact; (ii) because school children are younger it is harder for them to cope with remote learning, and (iii) because reopening schools freed up parents from childcare allowing other sectors of the economy to recover. However, if you disagree knock a quarter off all of the figures for the impact of universities.

Maybe not so bad – lockdowns and government policy

Finally, while the bald figure of one death for every 50 to 100 students educated is frighteningly large, there is I think there is a good argument to reduce this substantially, albeit opening up the issue of wider non-mortality costs for society.

Last autumn Covid cases were increasing rapidly and the UK government was set against any further control measures. Eventually it was forced to instigate a November lockdown across England after the earlier Wales ‘firebreak’. The trigger for this was not the cases per se, but the danger of overwhelming the NHS ability to cope.

Those on the front-line of the NHS would debate how close we got to breakdown, and indeed whether in many ways we went beyond it. However, crucially the driver of policy has been not Covid cases as such, nor even Covid deaths, but the number of hospital and especially intensive care admissions.

If Covid cases had been only half as high, there might not have been a pre-alpha lockdown at all before Christmas, or if there had been it would have been later as would the January lockdown.

By this argument, which I believe is a sound one, the impact of last year’s universities reopening was to accelerate growth, leading to earlier and longer lockdowns. The increase in university-attributable deaths would by this argument still not be negligible, but lower, maybe less than 10,000 (about one for every 250 students educated). However, this is then offset against the additional strain put on the rest of society, not least on the jobs of the other 50% of 18-21 year olds who don’t go to university.

In summary

First of all, it should be noted that there will be a further hit as universities return now, and a recent Times Higher survey reported that more than half of lecturers had serious concerns about the new term. However, the corresponding figures for this year will be an order of magnitude lower. This does not mean we should not take every precaution possible, Covid deaths are still at levels that would be inconceivable if we hadn’t seen them so much higher previously. At the time of writing, there are as many deaths due to Covid in two weeks as a whole year’s worth of road deaths.

As is probably evident, certainly from previous writing about the issue, I believe the decision to reopen the HE sector in Autumn 2020 was fundamentally wrong. As I have previously argued, the universities’ hands were largely tied, as were to a lesser extent the devolved governments, by decisions taken at Westminster. I assume that these decisions were partly party political (not wanting to alienate half of first-time voters) and partly financial (reducing the need to prop up the HE sector groaning under the increased costs of dealing with remote teaching).

The result of this was a worst of all possible worlds: bad for students who often ended up paying for semi-useless accommodation and being taught remotely during lockdowns anyway; bad for lecturers trying to cope with mixed models of teaching and the uncertainty of constantly switching of models; and bad for society deepening both the health and economic crisis.

Possibly saying that the universities’ hands were tied by government and that in turn as an employee of the university I was just continuing to do my job is a version of the concentration-camp guard excuse. Personally I feel the weight of this: I knew what was unfolding, I had written about it, but could I have done more to raise the issue?

Looking forward we can still make a difference.

I’m part of the Not-Equal research network focused on issues social justice in the digital economy. We are coming to the end of our funded period and had originally hoped to have an in-person end-of-project event bringing together the many academics and third-sector stake-holders who have been part of the network to share experiences and maybe create new partnerships looking forward. During the summer, after consulting with our advisory board, we unanimously decided to instead have a purely virtual event. Meeting together would have clearly had great advantages, but it felt that holding such an event, however worthy would be irresponsible.

Each such decision only makes a small difference, but it is the tens of thousands of such small acts that make a big difference. This has been one of the hard to comprehend lessons of Covid, but one that will continue to be important as we shift our focus back towards other massive issues of poverty, social injustice, climate change and the myriad diseases other than Covid that plague so many in the world.