Heidegger and hammers have been part of HCI’s conceptualisation from pretty much as long as I can recall. Although maybe I first heard the words at some sort of day workshop in the late 1980s as the hammer example as used in HCI annoyed me even then, so let’s start with hammers.

hammers

I should explain that problems with the hammer example are not my current struggles with Heidegger! For the hammer it is just that Heidegger’s ‘ready at hand’ is often confused with ‘walk up and use’. In Heidegger ready-at-hand refers to the way one is focused on the nail, or wood to be joined, not the hammer itself:

“The work to be produced is the “towards which” of such things as the hammer, the plane, and the needle” (Being and Time, p.70/99)

To be ‘ready to hand’ like this typically requires familiarity with the equipment (another big Heidegger word!), and is very different from the way a cash machine or tourist information systems should be in some ways accessible independent of prior knowledge (or at least only generic knowledge and skills).

My especial annoyance with the hammer example stems from the fact that my father was a carpenter and I reckon it took me around 10 years to learn how to use a hammer properly! Even holding it properly is not obvious, look at the picture.

There is a hand sized depression in the middle. If you have read Norman’s POET you will think, “ah yes perceptual affordance’, and grasp it like this:

But no that is not the way to hold it! If try to use it like this you end up using the strength of your arm to knock in the nail and not the weight of the hammer.

Give it to a child, surely the ultimate test of ‘walk up and use’, and they often grasp the head like this.

In fact this is quite sensible for a child as a ‘proper’ grip would put too much strain on their wrist. Recall Gibson’s definition of affordance was relational, about the ecological fit between the object and the potential actions, and the actions depends on who is doing the acting. For a small child with weaker arms the hammer probably only affords use at all with this grip.

In fact the ‘proper’ grip is to hold it quite near the end where you can use the maximum swing of the hammer to make most use of the weight of the hammer and its angular momentum:

Anyway, I think maybe Heidegger knew this even if many who quote him don’t!

Heidegger

OK, so its alright me complaining about other people mis-using Heidegger, but I am in the middle of writing one of the chapters for TouchIT and so need to make sure I don’t get it wrong myself … and there my struggles begin. I need to write about ready-to-hand and present-to-hand. I thought I understood them, but always it has been from secondary sources and as I sat with Being and Time in one hand, my Oxford Companion to Philosophy in another and various other books in my teeth … I began to doubt.

First of all what I thought the distinction was:

- ready at hand — when you are using the tool and it is invisible to you, you just focus on the work to be done with it

- present at hand — when there is some sort of breakdown, the hammer head is loose or you don’t have the right tool to hand and so start to focus on the tools themsleves rather than on the job at hand

Scanning the internet this is certainly what others think, for example blog posts at 251 philosophy and Matt Webb at Berg. Koschmann, Kuutti and Hickman produced an excellent comparison of breakdown in Heidegger, Leont’ev and Dewey, and from this it looks as though the above distinction maybe comes Dreyfus summary of Heidegger — but again I don’t have a copy of Dreyfus’ “Being-in-the-World“, so not certain.

Now this is an important distinction, and one that Heidegger certainly makes. The first part is very clearly what Heidegger means by ready-to-hand:

“The peculiarity of what is proximally to hand is that, in its readiness-to-hand, it must, as it were, withdraw … that with which we concern ourselves primarily is the work …” (B&T, p.69/99)

The second point Heidegger also makes at length distinguishing at least three kinds of breakdown situation. It just seems a lot less clear whether ‘present-at-hand’ is really the right term for it. Certainly the ‘present-at-hand’ quality of an artefact becomes foregrounded during breakdown:

“Pure presence at hand announces itself in such equipment, but only to withdraw to the readiness-in-hand with which one concerns oneself — that is to say, of the sort of thing we find when we put it back into repair.” (B&T, p.73/103)

But the preceeding sentance says

“it shows itself as an equipmental Thing which looks so and so, and which, in its readiness-to-hand as looking that way, has constantly been present-at-hand too.” (B&T, p.73/103)

That is present-at-hand is not so much in contrast to ready-at-hand, but in a sense ‘there all along’; the difference is that during breakdown the presence-at-hand becomes foregrounded. Indeed when ‘present-at-hand’ is first introduced Heidegger appears to be using it as a binary distinction between Dasein, (human) entities that exist and ponder their existence, and other entities such as a table, rock or tree (p. 42/67). The contrast is not so much between ready-to-hand and present-to-hand, but between ready-to-hand and ‘just present-at-hand’ (p.71/101) or ‘Being-just-present-at-hand-and-no-more’ (p.73/103). For Heidegger to seems not so much that ‘ready-to-hand’ stands in in opposition to ‘present-to-hand’; it is just more significant.

To put this in context, traditional philosophy had focused exclusively on the more categorically defined aspects of things as they are in the world (‘existentia’/present-at-hand), whilst ignoring the primary way they are encountered by us (Dasein, real knowing existence) as ready-to-hand, invisible in their purposefulness. Heidegger seeks to redress this.

“If we look at Things just ‘theoretically’, we can get along without understanding readiness-to-hand.” (B&T p.69/98)

Heidegger wants to avoid the speculation of previous science and philosophy. Although it is not a Heidegger word, I use ‘speculation’ here with all of its connotations, pondering at a distance, but without commitment, or like spectators at a sports stadium looking in at something distant and other. In contrast, ready-to-hand suggests commitment, being actively ‘in the world’ and even when Heidegger talks about those moments when an entity ceases to be ready-to-hand and is seen as present-to-hand, he uses the term circumspection — a casting of the eye around, so that the Dasein, the person, is in the centre.

So present-at-hand is simply the mode of being of the entities that are not Dasein (aware of their own existence), but our primary mode of experience of them and thus in a sense the essence of their real existence is when they are ready-to-hand. I note Roderick Munday’s useful “Glossary of Terms in Being and Time” highlights just this broader sense of present-at-hand.

Maybe the confusion arises because Heidegger’s concern is phenomenological and so when an artefact is ready-to-hand and its presence-to-hand ‘withdraws’, in a sense it is no longer present-to-hand as this is no longer a phenomenon; and yet he also seems to hold a foot in realism and so in another sense it is still present-to-hand. In discussing this tension between realism and idealism in Heidegger, Stepanich distinguishes present-at-hand and ready-to-hand, from presence-to-hand and readiness-to-hand — however no-one else does this so maybe that is a little too subtle!

To end this section (almost) with Heidegger’s words, a key statement, often quoted, seems to say precisely what I have argued above, or maybe precisely the opposite:

“Yet only by reason of something present-at-hand ‘is there’ anything ready-to-hand. Does it follow, however, granting this thesis for the nonce, that readiness-to-hand is ontologically founded upon presence-at-hand?” (B&T, p.71/101)

What sort of philosopher makes a key point through a rhetorical question?

So, for TouchIT, maybe my safest course is to follow the example of the Oxford Companion to Philosophy, which describes ready-to-hand, but circumspectly never mentions present-to-hand at all?

and anyway what’s wrong with …

On a last note there is another confusion, or maybe mistaken attitude, that seems to be common when referring to ready-to-hand. Heidegger’s concern was in ontology, understanding the nature of being, and so he asserted the ontological primacy of the ready-to-hand, especially in light of the previous dominant concerns of philosophy. However, in HCI, where we are interested not in the philosophical question, but the pragmatic one of utility, usability, and experience, Heidegger is often misapplied as a kind of fetishism of engagement, as if everything should be ready-to-hand all the time.

Of course for many purposes this is correct, as I type I do not want to be aware of the keys I press, not even of the pages of the book that I turn.

Yet there is also a merit in breaking this engagement, to encourage reflection and indeed the circumspection that Heidegger discusses. Indeed Gaver et al.’s focus on ambiguity in design is often just to encourage that reflection and questioning, bringing things to the foreground that were once background.

Furthermore as HCI practitioners and academics we need to both take seriously the ready-to-hand-ness of effective design, but also (just as Heidegger is doing) actually look at the ready-to-hand-ness of things seeing them and their use not taking them for granted. I constantly strive to find ways to become aware of the mundane, and offer students tools for estrangement to look at the world askance.

“To lay bare what is just present-at-hand and no more, cognition must first penetrate beyond what is ready-to-hand in our concern.” (B&T, p.71/101)

This ability to step out and be aware of what we are doing is precisely the quality that Schon recognises as being critical for the ‘Reflective Practioner‘. Indeed, my practical advice on using the hammer in the footnotes below comes precisely through reflection on hammering, and breakdowns in hammering, not through the times when the hammer was ready-to-hand..

Heidegger is indeed right that our primary existence is being in the world, not abstractly viewing it from afar. And yet, sometimes also, just as Heidegger himself did as he pondered and wrote about these issues, one of our crowning glories as human beings is precisely that we are able also in a sense to step outside ourselves and look in wonder.

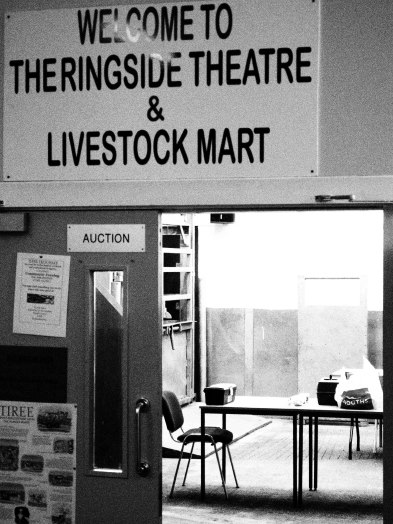

Just a week to go now before the next Tiree Tech Wave starts, although the first person is coming on Sunday and one person is going to hang on for a while after getting some surfing in.

Just a week to go now before the next Tiree Tech Wave starts, although the first person is coming on Sunday and one person is going to hang on for a while after getting some surfing in. At previous TTW we have had open evenings when people from the local community have come in to see what is being done. This time, as well as having a general welcome to people to come and see, Jonnet from HighWire at Lancaster is going to run a community workshop on mending based on her personal and PhD work on ‘Futuremenders‘. Central to this is Jonnet’s pledge to not acquire any more clothes, ever, but instead to mend and remake. This picks up on textile themes on the island especially the ‘Rags to Riches Eco-Chic‘ fashion award and community tapestry group, but also Tech Wave themes of making, repurposing and generally taking things to pieces. Jonnet’s work is not techno-fashion (no electroluminescent skirts, or LEDs stitched into your wooly hat), but does use social connections both physical and through the web to create mass participation, including mass panda knitting and an attempt on the world mass darning record.

At previous TTW we have had open evenings when people from the local community have come in to see what is being done. This time, as well as having a general welcome to people to come and see, Jonnet from HighWire at Lancaster is going to run a community workshop on mending based on her personal and PhD work on ‘Futuremenders‘. Central to this is Jonnet’s pledge to not acquire any more clothes, ever, but instead to mend and remake. This picks up on textile themes on the island especially the ‘Rags to Riches Eco-Chic‘ fashion award and community tapestry group, but also Tech Wave themes of making, repurposing and generally taking things to pieces. Jonnet’s work is not techno-fashion (no electroluminescent skirts, or LEDs stitched into your wooly hat), but does use social connections both physical and through the web to create mass participation, including mass panda knitting and an attempt on the world mass darning record.

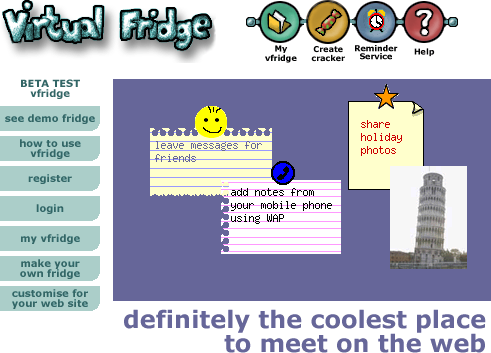

The core idea of vfridge is placing small notes, photos and ‘magnets’ in a shareable web area that can be moved around and arranged like you might with notes held by magnets to a fridge door.

The core idea of vfridge is placing small notes, photos and ‘magnets’ in a shareable web area that can be moved around and arranged like you might with notes held by magnets to a fridge door. Just over a year ago I thought it would be good to write a retrospective about vfridge in the light of the social networking revolution. We did a poster “

Just over a year ago I thought it would be good to write a retrospective about vfridge in the light of the social networking revolution. We did a poster “

I have just finished reading Schön’s “

I have just finished reading Schön’s “