The value of networks or graphs underlies many of the internet (and for that read global corporate) giants. Two of the biggest: Google and Facebook harness this in very different ways — mining and building.

Years ago, when I was part of the dot.com startup aQtive, we found there was no effective understanding of internet marketing, and so had to create our own. Part of this we called ‘market ecology‘. This basically involved mapping out the relationships of influence between different kinds of people within some domain, and then designing families of products that exploited that structure.

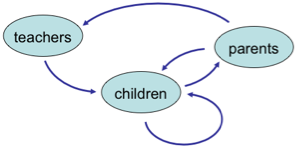

The networks we were looking at were about human relationships: for example teachers who teach children, who have other children as friends and siblings, and who go home to parents. Effectively we were into (too) early social networking1!

The first element of this was about mining — exploiting the existing network of relationships.

However in our early white papers on the topic, we also noted that the power of internet products was that it was also possible to create new relationships, for example, adding ‘share’ links. That is building the graph.

The two are not distinct, if one is not able to exploit new relationships within a product it will die, and the mining of existing networks can establish new links (e.g. Twitter suggesting who to follow). Furthermore, creating of links is rarely ex nihilo, an email ‘share’ link uses an existing relationships (contact in address book), but brings it into a potentially different domain (e.g. bookmarking a web page).

It is interesting to see Google and Facebook against this backdrop. Their core strengths are in different domains (web information and social relationships), but moreover they focus differently on mining and building.

Google is, par excellence, about mining graphs (the web). While it has been augmented and modified over the years, the link structure used in PageRank is what made Google great. Google also mine tacit relationships, for example the use of word collocation to understand concepts and relationships, so in a sense build from what they mine.

Facebook’s power, in contrast, is in the way it is building the social graph as hundreds of millions of people tell it about their own social relationships. As noted, this is not ex nihilo, the social relationships exist in the real word, but Facebook captures them digitally. Of course, then Facebook mines this graph in order to derive revenue form advertisements, and (although people debate this) attempt to improve the user experience by ranking posts.

Perhaps the greatest power comes in marrying the two. Amazon does this to great effect within the world of books and products.

As well as a long-standing academic interest, these issues are particularly germane to my research at Talis where the Education Graph is a core element. However, they apply equally whether the core network is kite surfers, chess or bio-technology.

Between the two it is probably building that is ultimately most critical. When one has a graph or network it is possible to find ways to exploit it, but without the network there is nothing to mine. Page and Brin knew this in the early days of their pre-Google project at Stanford, and a major effort was focused on simply gathering the crawl of the web on which they built their algorithms2. Now Google is aware that, in principle, others can exploit the open resources on which much of its business depends; its strength lies in its intellectual capital. In contrast, with a few geographical exceptions, Facebook is the social graph, far more defensible as Google has discovered as it struggles with Google Plus.

- See our retrospective about vfridge at last year’s HCI conference and our original web sharer vision.[back]

- See the description of this in “In The Plex: How Google Thinks, Works and Shapes Our Lives“.[back]