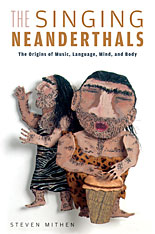

One of my birthday presents was Steven Mithin’s “The Singing Neanderthals” and, having been on holiday, I have already read it! I read Mithin’s “The Prehistory of the Mind” some years ago and have referred to it repeatedly over the years, so was excited to receive this book, and it has not disappointed. I like his broad approach taking evidence from a variety of sources, as well as his own discipline of prehistory; in times when everyone claims to be cross-disciplinary, Mithin truly is.

One of my birthday presents was Steven Mithin’s “The Singing Neanderthals” and, having been on holiday, I have already read it! I read Mithin’s “The Prehistory of the Mind” some years ago and have referred to it repeatedly over the years, so was excited to receive this book, and it has not disappointed. I like his broad approach taking evidence from a variety of sources, as well as his own discipline of prehistory; in times when everyone claims to be cross-disciplinary, Mithin truly is.

“The Singing Neanderthal”, as its title suggests, is about the role of music in the evolutionary development of the modern human. We all seem to be born with an element of music in our heart, and Mithin seeks to understand why this is so, and how music is related to, and part of the development of, language. Mithin argues that elements of music developed in various later hominids as a form of primitive communication, but separated from language in homo sapiens when music became specialised to the communication of emotion and language to more precise actions and concepts.

The book ‘explains’ various known musical facts, including the universality of music across cultures and the fact that most of us do not have perfect pitch … even though young babies do (p77). The hard facts of how things were for humans or related species tens or hundreds of thousands of years ago are sparse, so there is inevitably an element of speculation in Mithin’s theories, but he shows how many, otherwise disparate pieces of evidence from palaeontology, psychology and musicology make sense given the centrality of music.

Whether or not you accept Mithin’s thesis, the first part of the book provides a wide ranging review of current knowledge about the human psychology of music. Coincidentally, while reading the book, there was an article in the Independent reporting on evidence for the importance of music therapy in dealing with depression and aiding the rehabilitation of stroke victims, reinforcing messages from Mithin’s review.

The topic of “The Singing Neanderthal” is particularly close to my own heart as my first personal forays into evolutionary psychology (long before I knew the term, or discovered Cosmides and Tooby’s work), was in attempting to make sense of human limits to delays and rhythm.

Those who have been to my lectures on time since the mid 1990s will recall being asked to first clap in time and then swing their legs ever faster … sometimes until they fall over! The reason for this is to demonstrate the fact that we cannot keep beats much slower than one per second, and then explain this in terms of our need for a mental ‘beat keeper’ for walking and running. The leg shaking is to show how our legs, as a simple pendulum, have a natural frequency of around 1Hz, hence determining our slowest walk and hence need for rhythm.

Mithin likewise points to walking and running as crucial in the development of rhythm, in particular the additional demands of bipedal motion (p150). Rhythm, he argues, is not just about music, but also a shared skill needed for turn-taking in conversation (p17), and for emotional bonding.

In just the last few weeks, at the HCI conference in Newcastle, I learnt that entrainment, when we keep time with others, is a rare skill amongst animals, almost uniquely human. Mithin also notes this (p206), with exceptions, in particular one species of frog, where the males gather in groups to sing/croak in synchrony. One suggested reason for this is that the louder sound can attract females from a larger distance. This cooperative behaviour of course acts against each frog’s own interest to ‘get the girl’ so they also seek to out-perform each other when a female frog arrives. Mithin imagines that similar pressures may have sparked early hominid music making. As well as the fact that synchrony makes the frogs louder and so easy to hear, I wonder whether the discerning female frogs also realise that if they go to a frog choir they get to chose amongst them, whereas if they follow a single frog croak they get stuck with the frog they find; a form of frog speed dating?

Mithin also suggests that the human ability to synchronise rhythm is about ‘boundary loss’ seeing oneself less as an individual and more as part of a group, important for early humans about to engage in risky collaborative hunting expeditions. He cites evidence of this from the psychology of music, anthropology, and it is part of many people’s personal experience, for example, in a football crowd, or Last Night at the Proms.

This reminds me of the experiments where a rubber hand is touched in time with touching a person’s real hand; after a while the subject starts to feel as if the rubber hand is his or her own hand. Effectively our brain assumes that this thing that correlates with feeling must be part of oneself. Maybe a similar thing happens in choral singing, I voluntarily make a sound and simultaneously everyone makes the sound, so it is as if the whole choir is an extension of my own body?

Part of the neurological evidence for the importance of group music making concerns the production of oxytocin. In experiments on female prairie voles that have had oxytocin production inhibited, they engage in sex as freely as normal voles, but fail to pair bond (p217). The implication is that oxytocin’s role in bonding applies equally to social groups. While this explains a mechanism by which collaborative rhythmic activities create ‘boundary loss’, it doesn’t explain why oxytocin is created through rhythmic activity in the first place. I wonder if this is perhaps to do with bipedalism and the need for synchronised movement during face-to-face copulation, which would explain why humans can do synchronised rhythms whereas apes cannot. That is, rhythmic movement and oxytocin production become associated for sexual reasons and then this generalises to the social domain. Think again of that chanting football crowd?

I should note that Mithin also discusses at length the use of music in bonding with infants, as anyone who has sung to a baby knows, so this offers an alternative route to rhythm & bonding … but not one that is particular to humans, so I will stick with my hypothesis 😉

Sexual selection is a strong theme in the book, the kind of runaway selection that leads to the peacock tail. Changing lifestyles of early humans, in particular longer periods looking after immature young, led to a greater degree of female control in the selection of partners. As human size came close to the physical limits of the environment (p185), Mithin suggests that other qualities had to be used by females to choose their mate, notably male singing and dance – prehistoric Saturday Night Fever.

As one evidence for female mate choice, Mithin points to the overly symmetric nature of hand axes and imagines hopeful males demonstrating their dexterity by knapping ever more perfect axes in front of admiring females (p188). However, this brings to mind Calvin’s “Ascent of Mind“, which argues that these symmetric, ovoid axes were used like a discus, thrown into the midst of a herd of prey to bring one down. The two theories for axe shape are not incompatible. Calvin suggests that the complex physical coordination required by axe throwing would have driven general brain development. In fact these forms of coordination, are not so far from those needed for musical movement, and indeed expert flint knapping, so maybe it was this skills that were demonstrated by the shaping of axes beyond that immediately necessary for purpose.

Mithin’s description of the musical nature of mother-child interactions also brought to mind Broomhall’s “Eternal Child“. Broomhall ‘s central thesis is that humans are effectively in a sort of arrested development with many features, not least our near nakedness, characteristic of infants. Although it was not one of the points Broomhall makes, his arguments made sense to me in terms of the mental flexibility that characterises childhood, and the way this is necessary for advanced human innovation; I am always encouraging students to think in a more childlike way. If Broomhall’s theories were correct, then this would help explain how some of the music making more characteristic of mother-infant interactions become generalised to adult social interactions.

I do notice an element of mutual debunking amongst those writing about richer cognitive aspects of early human and hominid development. I guess a common trait in disciplines when evidence is thin, and theories have to fill a lot of blanks. So maybe Mithin, Calvin and Broomhall would not welcome me bringing their respective contributions together! However, as in other areas where data is necessarily scant (such as sub-atomic physics), one does feel a developing level of methodological rigour, and the fact that these quite different theoretical approaches have points of connection, does suggest that a deeper understanding of early human cognition, while not yet definitive, is developing.

In summary, and as part of this wider unfolding story, “The Singing Neanderthal” is an engaging and entertaining book to read whether you are interested in the psychological and social impact of music itself, or the development of the human mind.

… and I have another of Mithin’s books in the birthday pile, so looking forward to that too!

One of my birthday presents was Steven Mithin’s “

One of my birthday presents was Steven Mithin’s “