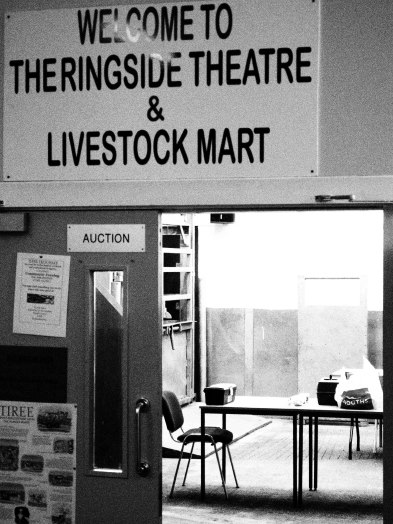

The Second Tiree Tech Wave is over. Yesterday the last participants left by ferry and plane and after a final few hours tidying, the Rural Centre, which the day before had been a tangle of wire and felt, books and papers, cups and biscuit packets, is now as it had been before. And as I left, the last boxes under my arm, it was strangely silent with only the memory of voices and laughter in my mind.

The Second Tiree Tech Wave is over. Yesterday the last participants left by ferry and plane and after a final few hours tidying, the Rural Centre, which the day before had been a tangle of wire and felt, books and papers, cups and biscuit packets, is now as it had been before. And as I left, the last boxes under my arm, it was strangely silent with only the memory of voices and laughter in my mind.

So is it as if it had never been? I there anything left behind? There are a few sheets of Magic Whiteboard on the walls, that I left so that those visiting the Rural Centre in the coming weeks can see something of what we were doing, and there are used teabags and fish-and-chip boxes in the bin, but few traces.

We trod lightly, like the agriculture of the island, where Corncrake and orchid live alongside sheep and cattle.

Some may have heard me talk about the way design is like a Spaghetti Western. In the beginning of the film Clint Eastwood walks into the town, and at the end walks away. He does not stay, happily ever after, with a girl on his arm, but leaves almost as if nothing had ever happened.

But while he, like the designer, ultimately leaves, things are not the same. The Carson brothers who had the town in fear for years lie dead in their ranch at the edge of town, the sharp tang of gunfire still in the air and the buzz of flies slowly growing over the elsewise silent bodies. The crooked major, who had been in the pocket of the Carson brothers, is strapped over a mule heading across the desert towards Mexico, and not a few wooden rails and water buts need to be repaired. The job of the designer is not to stay, but to leave, but leave change: intervention more than invention.

But the deepest changes are not those visible in the bullet-pocked saloon door, but in the people. The drunk who used to sit all day at the bar, has discovered that he is not just a drunk, but he is a man, and the barmaid, who used to stand behind the bar has discovered that she is not just a barmaid, but she is a woman.

This is true of the artefacts we create and leave behind as designers, but much more so of the events, which come and go through our lives. It is not so much the material traces they leave in the environment, but the changes in ourselves.

I know that, as the plane and ferry left with those last participants, a little of myself left with them, and I know many, probably all, felt a little of themselves left behind on Tiree. This is partly abut the island itself; indeed I know one participant was already planning a family holiday here and another was looking at Tiree houses for sale on RightMove! But it was also the intensity of five, sometimes relaxed, sometimes frenetic, days together.

So what did we do?

There was no programme of twenty minute talks, no keynotes or demo, indeed no plan nor schedule at all, unusual in our diary-obsessed, deadline-driven world.

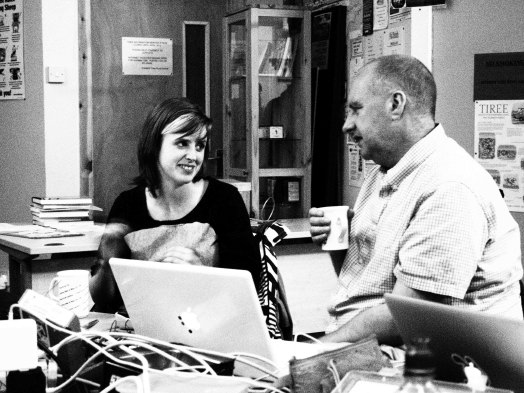

Well, we talked. Not at a podium with microphone and Powerpoint slides, but while sitting around tables, while walking on the beach, and while standing looking up at Tilly, the community wind turbine, the deep sound of her swinging blades resonating in our bones. And we continued to talk as the sun fell and the overwhelmingly many stars came out , we talked while eating, while drinking and while playing (not so expertly) darts.

We met people from the island those who came to the open evening on Saturday, or popped in during the days, and some at the Harvest Service on Sunday. We met Mark who told us about the future plans for Tiree Broadband, Jane at PaperWorks who made everything happen, Fiona and others at the Lodge who provided our meals, and many more. Indeed, many thanks to all those on the island who in various ways helped or made those at TTW feel welcome.

We also wrote. We wrote on sheets of paper, notes and diagrams, and filled in TAPT forms for Clare who was attempting unpack our experiences of peace and calmness in the hope of designing computer systems that aid rather than assault our solitude. Three large Magic Whiteboard sheets were entitled “I make because …”, “I make with …”, “I make …” and were filled with comments. And, in these days of measurable objectives, I know that at least a grant proposal, book chapter and paper were written during the long weekend; and the comments on the whiteboards and experiences of the event will be used to create a methodological reflection of the role of making in research which we’ll put into Interfaces and the TTW web site.

We moved. Walking, throwing darts, washing dishes, and I think all heavily gesturing with our hands while taking. And became more aware of those movements during Layda’s warm-up improvisation exercises when we mirrored one another’s movements, before using our bodies in RePlay to investigate issues of creativity and act out the internal architecture of Magnus’ planned digital literature system.

We directly encountered the chill of wind and warmth of sunshine, the cattle and sheep, often on the roads as well as in the fields. We saw on maps the pattern of settlement on the island and on display boards the wools from different breeds on the island. Some of us went to the local historical centre, An Iodhlann [[ http://www.aniodhlann.org.uk/ ]], to see artefacts, documents and displays of the island in times past, from breadbasket of the west of Scotland to wartime airbase.

We slept. I in my own bed, some in the Lodge, some in the B&B round the corner, Matjaz and Klem in a camper van and Magnus – brave heart – in a tent amongst the sand dunes. Occasionally some took a break and dozed in the chairs at the Rural Centre or even nodded off over a good dinner (was that me?).

We showed things we had brought with us, including Magnus’ tangle of wires and circuit boards that almost worked, myself a small pack of FireFly units (enough to play with I hope in a future Tech Wave), Layda’s various pieces she had made in previous tech-arts workshops, Steve’s musical instrument combining Android phone and cardboard foil tube, and Alessio’s impressively modified table lamp.

And we made. We do after all describe this as a making event! Helen and Claire explored the limits of ZigBee wireless signals. Several people contributed to an audio experience using proximity sensors and Arduino boards, and Steve’s CogWork Chip: Lego and electronics, maybe the world’s first mechanical random-signal generator. Descriptions of many of these and other aspects of the event will appear in due course on the TTW site and participants’ blogs.

But it was a remark that Graham made as he was waiting in the ferry queue that is most telling. It was not the doing that was central, the making, even the talking, but the fact that he didn’t have to do anything at all. It was the lack of a plan that made space to fill with doing, or not to do so.

Is that the heart? We need time and space for non-doing, or maybe even un-doing, unwinding tangles of self as well as wire.

There will be another Tiree Tech Wave in March/April, do come to share in some more not doing then.

Who was there:

Alessio Malizia – across the seas from Madrid, blurring the boundaries between information, light and space

Alessio Malizia – across the seas from Madrid, blurring the boundaries between information, light and space- Helen Pritchard – artist, student of innovation and interested in cows

- Claire Andrews – roller girl and researching the design of assistive products

- Clare Hooper – investigating creativity, innovation and a sprinkling of SemWeb

- Magnus Lawrie – artist, tent-dweller and researcher of digital humanities

- Steve Gill – designer, daredevil and (when he can get me to make time) co-authoring book on physicality TouchIT

- Graham Dean – ex-computer science lecturer, ex-businessman, and current student and auto-ethnographer of maker-culture

- Steve Foreshaw – builder, artist, magician and explorer of alien artefacts

- Matjaz Kljun – researcher of personal information and olive oil maker

- Layda Gongora – artist, curator, studying improvisation, meditation and wild hair

- Alan Dix – me

I was just reading the chapter on

I was just reading the chapter on