This, the last of my series of posts on post-REF analysis, asks what went wrong and what could be done to improve things in future.

Spoiler: a classic socio-technical failure story: compromising the quality of human processes in order to feed an algorithm

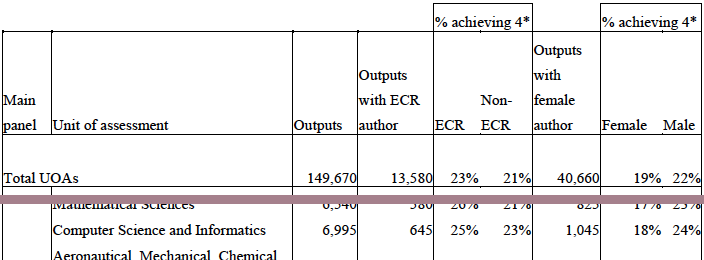

As I’ve noted multiple times, the whole REF process and every panel member was focused around fairness and transparency, and yet still the evidence is that quite massive bias emerged. This is evident in my own analysis of sub-area and institutional differences, and also in HEFCE’s own report, which highlighted gender differences.

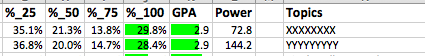

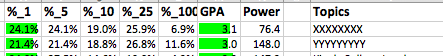

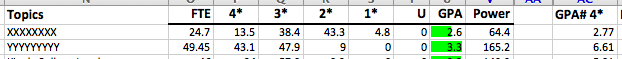

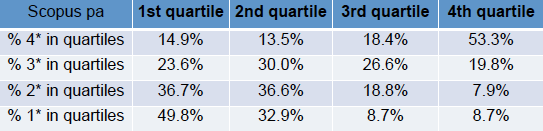

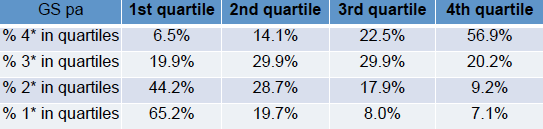

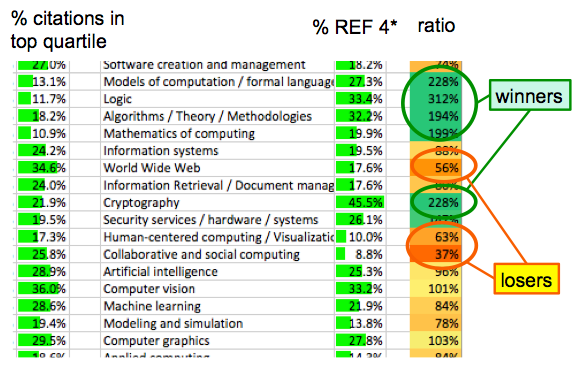

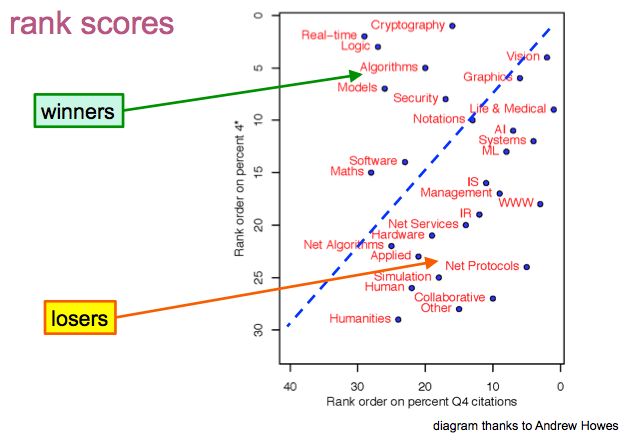

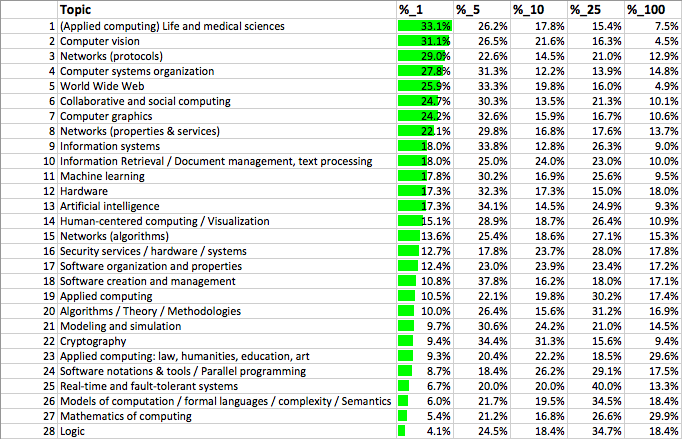

Summarising some of the effects we have seen in previous posts:

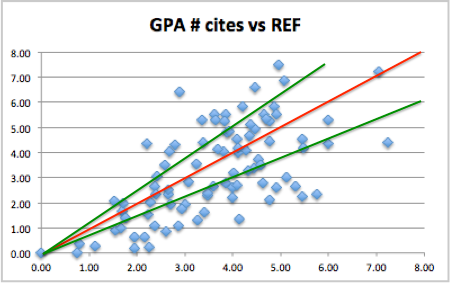

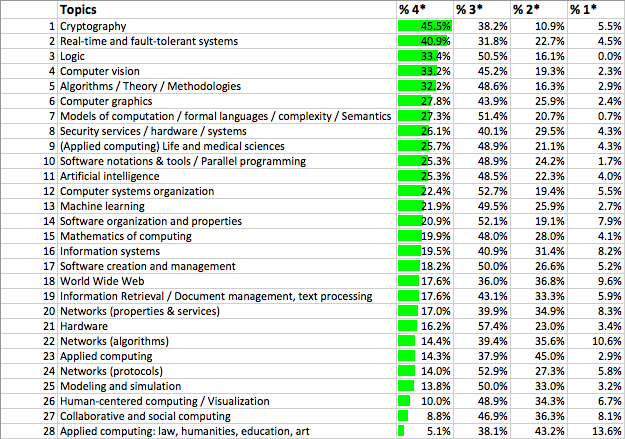

- sub-areas: When you rank outputs within their own areas worldwide: theoretical papers ranked in the top 5% (top 1 in 20) worldwide get a 4* of whereas those in more applied human/centric papers need to be in the top 0.5% (top 1 in 200) – a ten-fold difference (REF Redux 2)

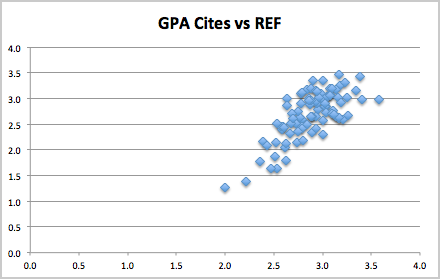

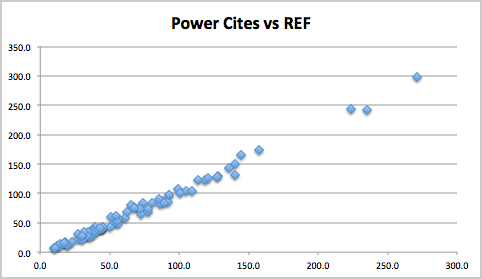

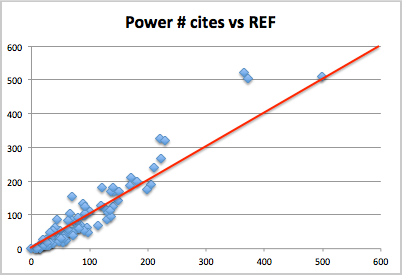

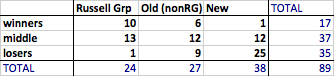

- institutions: Outputs that appear equivalent in terms of citation are ranked more highly in Russell Group universities compared with other old (pre-1992) universities, and both higher than new (post-1992) universities. If two institutions have similar citation profiles, the Russell Group one, on average, would receive 2-3 times more money per member of staff than the equivalent new university (REF Redux 4)

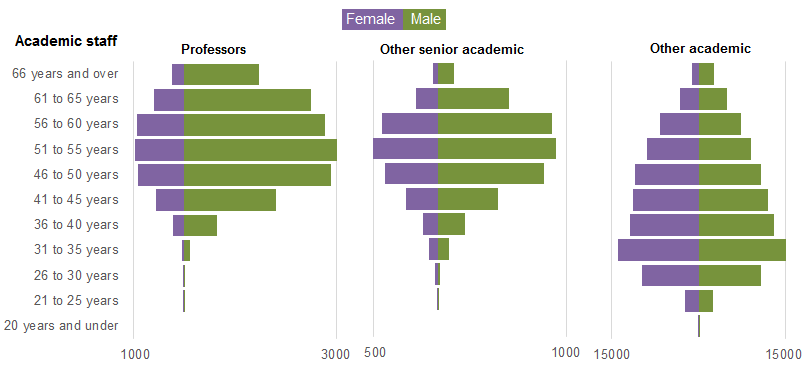

- gender: A male academic in computing is 33% more likely to get a 4* then a female academic, and this effect persists even when other factors considered (HEFCE report “The Metric Tide”). Rather than explicit bias, I believe this is likely to be an implicit bias due to the higher proportions of women in sub-areas disadvantaged by REF (REF Redux 5)

These are all quite shocking results, not so much that the differences are there, but because of the size.

Before being a computer scientist I was trained as a statistician. In all my years both as a professional statistician, and subsequently as a HCI academic engaged in or reviewing empirical work, I have never seen effect sizes this vast.

What went wrong?

Note that this analysis is all for sub-panel 11 Computer Science and Informatics. Some of the effects (in particular institutional bias) are probably not confined to this panel; however, there are special factors in the processes we used in computing which are likely to have exacerbated latent bias in general and sub-area bias in particular.

As a computing panel, we of course used algorithms!

The original reason for asking submissions to include an ACM sub-area code was to automate reviewer allocation. This meant that while other panel chairs were still starting their allocation process, SP11 members already had their full allocations of a thousand or so outputs a piece. Something like 21,000 output allocations at the press of a button. Understandably this was the envy of other panels!

We also used algorithms for normalisation of panel members’ scores. Some people score high, some score low, some bunch towards the middle with few high and few low scores, and some score too much to the extremes.

This is also the envy of many other panel members. While we did discuss scores on outputs where we varied substantially, we did not spend the many hours debating whether a particular paper was 3* or 4*, or trying to calibrate ourselves precisely — the algorithm does the work. Furthermore the process is transparent (we could even open source the code) and defensible — it is all in the algorithm, no potentially partisan decisions.

Of course such an algorithm cannot simply compare each panel member with the average as some panel members might have happened to have better or worse set of outputs to review than others. In order to work there has to be sufficient overlap between panel members’ assessments so that they can be robustly compared. In order to achieve this overlap we needed to ‘spread our expertise’ for the assignment process, so that we reviewed more papers slightly further from our core area of competence.

Panels varies substantially in the way they allocated outputs to reviewers. In STEM areas the typical output was an article of, say, 8–10 pages; whereas in the humanities often books or portfolios; in performing arts there might even be a recording of a performance taking hours. Clearly the style of reviewing varied. However most panels tried to assign two expert panelists to each output. In computing we had three assessors per output, compared to two in many areas (and in one sub-panel a single assessor per output). However, because of the expertise spreading this meant typically one expert and two more broad assessors per output.

For example, my own areas of core competence (Human-centered computing / Visualization and Collaborative and social computing) had between them 700 outputs, and were two others assessors with strong knowledge in these areas. However, of over 1000 outputs I assessed, barely one in six (170) were in these areas, that is only 2/3 more than if the allocation had been entirely random.

Assessing a broad range of computer science was certainly interesting, and I feel I came away with an understanding of the current state of UK computing that I certainly did not have before. Also having a perspective from outside a core area is very valuable especially in assessing the significance of work more broadly within the discipline.

This said the downside is that the vast majority of assessments were outside our core areas, and it is thus not so surprising that default assessments (aka bias) become a larger aspect of the assessment. This is particularly problematic when there are differences in methodology; whereas it is easy to look at a paper with mathematical proofs in it and think “that looks rigorous”, it is hard for someone not used to interpretative methodologies to assess, for example, ethnography.

If the effects were not so important, it is amusing to imagine the mathematics panel with statisticians, applied and pure mathematicians assessing each others work, or indeed, if formal computer science were assessed by a pure mathematicians.

Note that the intentions were for the best trying to make the algorithm work as well as possible; but the side effect was to reduce the quality of the human process that fed the algorithm. I recall the first thing I ever learnt in computing was the mantra, “garbage in — garbage out”.

Furthermore, the assumption underlying the algorithm was that while assessors differed in their severity/generosity of marking and their ‘accuracy’ of marking, they were all equally good at all assessments. While this might be reasonable if we all were mainly marking within our own competence zone, this is clearly not valid given the breadth of assessment. That is the fundamental assumptions of the algorithm were broken.

This is a classic socio-technical failure story: in an effort to ‘optimise’ the computational part of the system, the overall human–computer system was compromised. It is reasonable for those working in more purely computational areas to have missed this; however, in retrospect, those of us with a background in this sort of issue should have foreseen problems (John 9:41), mea culpa. Indeed, I recall that I did have reservations, but had hoped that any bad effects would average out given so many points of assessment. It was only seeing first Morris Sloman’s analysis and then the results of my own that I realised quite how bad the distortions had been.

I guess we fell prey to another classic systems failure: not trialling, testing or prototyping a critical system before using it live.

What could be done better?

Few academics are in favour of metrics-only systems for research assessment, and, rather like democracy, it may be that the human-focused processes of REF are the worst possible solution apart from all the alternatives.

I would certainly have been of that view until seeing in detail the results outlined in this series. However, knowing what I do now, if there were a simple choice for the next REF of what we did and a purely metrics-based approach, I would vote for the latter. In every way that a pure metrics based approach would be bad for the discipline, our actual process was worse.

However, the choice is not simply metrics vs human assessment.

In computing we used a particular combination of algorithm and human processes that amplified rather than diminished the effects of latent bias. This will have been particularly bad for sub-areas where differences in methodology lead to asymmetric biases. However, it is also likely to have amplified institution bias effects as when assessing areas far from one’s own expertise it is more likely that default cues, such as the ‘known’ quality of the institution, will weigh strongly.

Clearly we need to do this differently next time, and other panels definitely ought not to borrow SP11’s algorithms without substantial modification.

Maybe it is possible to use metrics-based approaches to feed into a human process in a way that is complimentary. A few ideas could be:

- metrics for some outputs — for example we could assess older journal and conference outputs using metrics, combined with human assessment for newer or non-standard outputs

- metrics as under-girding – we could give outputs an initial grade based on metrics, which is then altered after reading, but where there is a differential burden of proof — easy to raise a grade (e.g. because of badly chosen venue for strong paper), but hard to bring it down (more exceptional reasons such as citations saying “this paper is wrong”)

- metrics for in-process feedback — a purely human process as we had, but part way through calculate the kinds of profiles for sub-areas and institutions that I calculated in REF Redux 2, 3 and 4. At this point the panel would be able to decide what to do about anomalous trends, for example, individually examine examples of outputs.

There are almost certainly other approaches, the critical thing is that we must do better than last time.